|

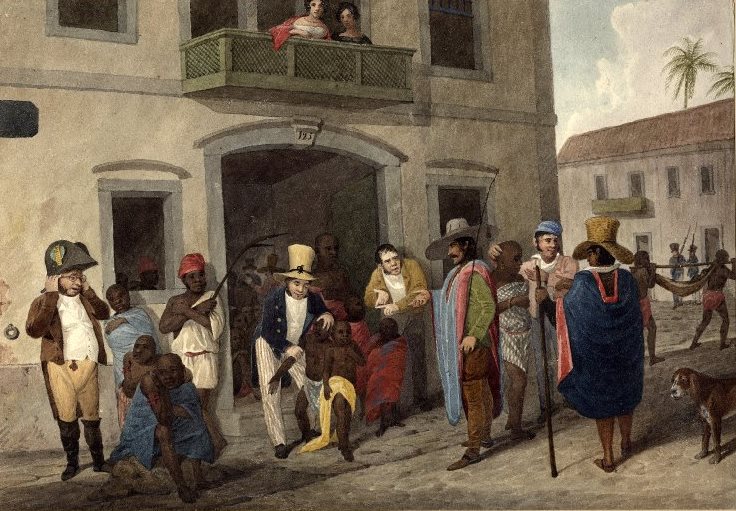

Originally posted in the Urban Studies Journal blog on May 6, 2021. This blog is on an article in Urban Studies. Click here to access the article. In 2007, Brazil was selected by FIFA as the host country for the 2014 World Cup, which included Rio de Janeiro among the country’s 12 host cities. Two years later, in 2009, the International Olympic Committee announced that Rio would also host the 2016 Olympics. As Brazil prepared to host these major mega-events by fashioning ‘hypermodern’ urban spaces, preparatory developments in Rio’s port area aimed to position the city as a centre of global competition and capitalism. One of its most iconic buildings, the Museum of Tomorrow, shown below, exemplifies this ambition. To do this, urban revitalization projects function as a form of public-private partnership — known in Brazil as operação urbana consorciada — allowing financialization and real estate speculation through relaxed zoning conditions in specific areas, which were ironically allowed through Brazil’s progressive urban legislation, the Statute of the City. Urban revitalization projects often disregard their impact on ethnic minority groups, race relations and the segregatory history of such processes. Even more than the displacement that often results, the link between hypermodernity and race are explicitly produced through mega-event processes. These large-scale developments in Rio came at a cost for the African and Afro-Brazilian communities that existed long before in the area. In this article, we document how Rio’s revitalization of the port area has literally buried the history of the transatlantic slave trade by reframing the narrative through discursive tactics. In Rio’s port area, despite the area’s abandonment and considerable recent challenges, Valongo Wharf is an important landmark as it was the entry point for as many as 900,000 African slaves into Rio. In 2017, UNESCO recognized Valongo as a World Heritage site. The site is part of the African Heritage Circuit promoted through CDURP, the company sponsoring the mega-revitalization project. Conversely, the Cemitério dos Pretos Novos — active from 1769 to 1830 in the area known as “Little Africa” — was a mass grave cemetery for enslaved Africans who died upon arrival. Discovered in 1996, it took years for the site to be officially recognized. This most significant archeological and historical site receives much less attention and resources. While CDURP invested three quarters of its cultural budget in the Museum of Tomorrow and the Rio Art Museum, the Institute to preserve the cemetery received minimum support, struggling to keep its doors open. The multiple contradictions produced through the dualisms we document in Porto Maravilha prompted us to identify the need for a special form of participation that we term legacy participation, which is distinct from participatory planning. Legacy participation highlights the need for Afro-Brazilian decision-making power through jurisdictional authority. We borrow such ideas from indigenous land rights literature, and argue that such forms of devolution could — and should — apply to the context of territorialized African heritage, such as the case of Porto Maravilha. Museum of Tomorrow (Museu do Amanhã). Source: By Domínio Público - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45719417 A slave market in Rio de Janeiro, by Edward Francis Finden, 1824

Source: http://usslave.blogspot.it/2011/08/slave-market-at-rio.html

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly