|

Originally posted in Panoramas.

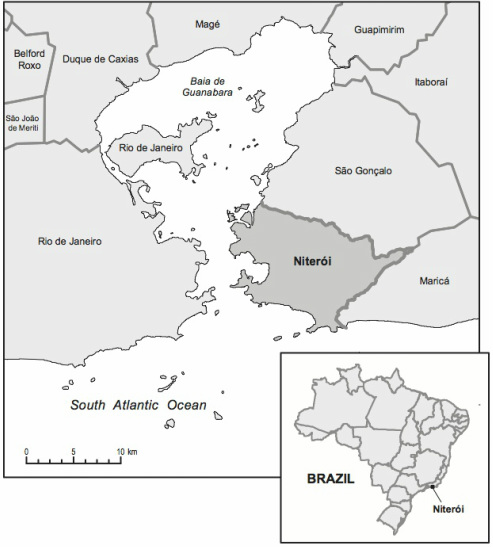

Protest movements in response to a range of issues have been in the spotlight in Brazil over the past three years, prompting considerable discussion about the future of collective action for the country. Drawing on research that occurred before the large-scale 2013 mobilizations occurred, this article in Latin American Research Review attempts to make sense of a perceived decline in social movement activity in urban centres in Brazil, arguing that such alterations result from a changing political context. It attempts to make sense of the many waves of civil society activity in the urban context, based on the idea of a cycle of protests (Tarrow, 1994). Brazil is a particular case where urban social movement activity has been much less significant in recent years than the social movements that emerged in the countryside such as the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), a phenomenon that Souza (2016) has discussed recently. The 2013 protests were the first massive protests in Brazilian cities since at least the Diretas Já movement in 1983-84 (the campaign for direct elections that ended 20 years of military rule). The article focuses on Niterói, a city of about a half-million people across the bay from Rio de Janeiro. Although civil society flourished until the 1990s in Niterói, many interviewees noted that the dynamism that had previously existed in the city was no longer present. Some referred to passivity, others mentioned retracted participation, while others talked about the movements’ “decay.” Given the need for a vibrant civil society in taking forward the goals of the urban reform movement in Brazil, this concern prompted an exploration to more analytically describe the nature of this decay. The urban reform movement, discussed in this article, initiated in the 1980s and composed of popular movements, neighborhood associations, NGOs, trade unions and professional organizations, helped to formulate a proposal for urban reform in the National Constituent Assembly. Ultimately, the movement was integral in helping to approve the Statute of the City in 2001, the national law that provides planning tools for cities based on a social justice approach. As a result, part of this interest in social movements stemmed from a contention of the important role of civil society in both the Brazilian Constitution (1988) building process and in the approval of the Statute of the City. In that sense, this is a very urban story that has played out in Brazil over several decades. This article was written and researched well before Brazilians came out in droves to protest, in part, a gap between theory and practice in June 2013. The June 2013 protests erupted in São Paulo against rising bus fares and were followed by similar protests across Brazil, highlighting the urban nature of the protests (Friendly, 2016). Since writing this article, much has changed in the world of urban social movements in Brazil as well as the political context. As the world watched Brazil prepare for and host the Rio Olympic Games, the economy slumped alongside an ongoing corruption crisis that resulted in, among other things, President Dilma Rousseff being removed from office. In addition to the protests that began in June 2013 to oppose rising bus fares, Brazilians have continued going to the streets to oppose rising transportation costs, corruption, the right to the city in general and the poor economic situation. Following Rousseff’s impeachment, protesters haven’t let up against Michel Temer’s interim government. One of the interesting things that has emerged in all of these events is that the protests at various points in time have come from both the political right and left. These events highlight a key conclusion of the article: that civil society changes and adapts based on the political context, including external opportunities. This approach connects the emergence and decline of protest cycles with political, institutional and cultural changes as key elements in understanding these changing dynamics. Given all the changes that have taken place over the past couple of years in Brazil, it is indeed a key moment for the country, but it is unlikely that civil society in Brazil will be as complacent as perceived in the case of Niterói. There is no question that civil society is playing a key role, but as this paper has argued, the political situation has also changed, redrawing a central element to these shifting dynamics. References Friendly, Abigail 2016 “Urban Policy, Social Movements and the Right to the City in Brazil.” Latin American Perspectives doi: 0094582X16675572. Souza, Marcel Lopes de 2016 “Social Movements in Brazil in Urban and Rural Contexts: Potentials, Limits and “Paradoxes.” In The Political System of Brazil, edited by D. de la Fontaine and T. Stehnken, 229-252. New York: Springer. Tarrow, Sidney 1994 Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Friendly, Abigail. 2016. “The Changing Landscape of Civil Society in Niterói, Brazil.” Latin American Research Review51(1): 218-241. DOI: 10.1353/lar.2016.0012

0 Comments

Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com (Excerpt from “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil” inPlanning Theory & Practice by Abigail Friendly). Although Brazil is notorious for its spatially segregated cities and high levels of inequality, a number of urban policy initiatives have evolved there since the 1990s, providing insights into how cities might improve life for city dwellers. In the wake of a twenty-year dictatorship, social movements in Brazil gained force during the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in a robust urban reform movement. This process of re-democratization led to the promulgation of a new ‘citizens’ Constitution in 1988, which included, for the first time, a specific chapter on urban policy. During this period, Brazil underwent rapid urbanization – its urban population climbed from 44.6% in 1960 to 84.3% in 2010 – alongside growth in social inequality, socio-spatial segregation and unplanned development (IBGE, 2010; Maricato, 2008; Rolnik, 2001; Santos, 2002). It is in this context – post-dictatorship, re-democratization and the forceful Brazilian social movements – that one new Brazilian urban policy has garnered international attention. Throughout the 1990s the urban reform movements maintained momentum, and on July 10, 2001 the Statute of the City was enacted. This formal incorporation of the right to the city into national law is unprecedented and unique, deriving from the concept of French sociologist Henri Lefebvre on the right to the city as a process and a struggle in the realm of every day life and, from the right to the city movement, as a right to participate in the production of urban space (Lefebvre, 1968, 1996; Mayer, 2012). In the Brazilian context, the right to the city means the combination of the principles of the ‘social function of property and of the city’ and the democratic management of cities (Fernandes, 2011). This can be interpreted as a mandate to guarantee the well-being of all city residents and the democratic access to goods and services produced in cities (Bassul, 2005; Filho, 2009). The Statute captures a new model of urban planning and management, a huge change in outlook from the old planning model grounded in modernism that prevailed between the 1940s and 1980s in Brazil, which resulted in a structure of urban inequality and exclusion by governing without generating social equality nor including the population in the process (Caldeira & Holston, 2005; Maricato, 1997). Among international observers, policy makers, academics, planners and activists, there is no question that the Statute is an innovative law from the standpoint of its legal and urban advances (Carvalho, 2001; Fernandes, 2007; Filho, 2009; Pindell, 2006; Souza, 2006). Certainly, the passing of the Statute inspired hope from both observers and participants. It has been called “remarkable in the history of urban legislation, policy, and planning not only in Brazil but worldwide” (Holston, 2008: 292) and an “inspiring example“ of action by national governments (Fernandes, 2007: 212). The literature thus far has focused on the legal and urban implications of the right to the city in Brazil as well as the social movements involved in this process (Avritzer, 2007; Caldeira & Holston, 2005; Fernandes, 2007; Pindell, 2006; Souza, 2001). However, the connection between this landmark right to the city legislation and an analysis of the practical on-the-ground implications of the Statute has not yet been evaluated. This paper includes an overview of what the right to the city means in theory, followed by an exploration of the Brazilian experience in implementing the right to the city. Based on data from my field work in Niterói in the State of Rio de Janeiro (shown in Figure 2), I explore the challenges in the Brazilian planning framework; in particular, the lack of implementation of the Statute of the City. I use the experience of one city, Niterói, to understand the possibilities and challenges involved in implementing the directives of the Statute of the City. The goal of this paper is twofold: first, I argue that the incorporation of the right to the city in a legal framework such as the Statute is unprecedented and unique and thus deserves recognition; second, in reflecting on the poor implementation of the Statute of the City in cities in Brazil, I argue that a more nuanced approach is needed in understanding the changes that have taken place in Brazil’s urban policy and planning over the past twenty years. Viewing the Brazilian urban climate since the period of military dictatorship in the 1980s, the country has come a long way with many advances; among them the Constitution, the Statute of the City and interesting experiences of urban policy in various cities. In that sense this story needs to be viewed as a process at one point along a long road. The approval of the Statute is only the first step. Its adoption on the part of the popular movements and local administrations was no small achievement and much more can be expected to result from this experience in future years. There have been significant changes in Brazil in terms of the role of planning, the production of urban space and the role of the state since the new Constitution. The results have significantly changed the planning model in Brazil to one focused on democratic spaces with “the potential to generate urban spaces that are less segregated and that fulfill their ‘social function’” (Caldeira & Holston, 2005: 411). Thus, Ermínia Maricato (2010: 22), a key policy-maker and academic deeply involved in the development of the Statute, notes that “regardless of the difficulty of implementing the City Statute, we believe that it is nevertheless the harbinger of a new and different future.” This suggests that what is needed is a nuanced approach to understanding the progress of the Statute of the City in Brazil. Combined with utopian Lefebvrian ideals, which do not fully explore how to practically implement the right to the city, such nuance is key.

In this paper I make the case for the unprecedented and unique incorporation of the right to the city as a key part of the fabric of the Statute of the City. Moreover, the role of civil society in pushing for the right to the city as a key component of the Statute is both compelling and educational for planning theory and practice, as it shows that bottom-up movements can produce policy change with the potential to affect the social fabric of urban life. In the paper, I outline some preliminary problems leading to poor implementation of the Statute of the City that emerged from my field work in Niterói. As a positive example of an innovative urban policy tool, both the Statute’s ideal – upholding the right to the city – and the results of its implementation, should be better known within the broader planning community. The Statute of the City captures a model of urban planning and management that is unique, not only in Brazil, but also worldwide. However, the implementation problems do not mean that learning experiences have not emerged from the Brazilian experience. Despite the implementation difficulties, this model of participatory planning may provide useful lessons for designing participatory planning, and it suggests ways in which the right to the city can be guaranteed for all. The planning model in Brazil is, indeed, a framework that could be applied in other locales. Despite contextual variations between countries, the Statute’s principles – based on the right to the city and the social function of property – could be transferred to other contexts with the recognition that policies, as socio-spatial processes, may actually change as they travel (McCann & Ward, 2011; Peck & Theodore, 2001). Despite Brazil’s advances in law, guaranteeing planning and land use, in practice, the lack of implementation has been challenging, as the case of Niterói suggests. This paper explores the right to the city in theory and practice, arguing for due recognition of this landmark legal and urban framework. Although in Brazil it has become common to argue that the Statute is still too recent to evaluate and address the clear problems in its implementation, criticism and discussion regarding the practical applications of the Statute are healthy and needed components of the debate in order to improve the practice of the right to the city. While the euphoria that surrounded the Statute during the 1990s no longer exists in Brazil, the climate is ripe for a new discussion about how to move beyond and to make the Statute of the City truly effective. Overall, the experience of applying the right to the city in Brazil takes the theoretical (and inherently utopian) concept as Lefebvre conceived it, forward, pointing to the challenges of implementing such policies in practice, but also pointing to experiences which could be used to inform planning practice elsewhere. For the full text of the article, “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil” in Planning Theory & Practice, see http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.783098. 1 Known as ‘Estatuto da Cidade,’ or Law No 10.257. Seehttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/LEIS_2001/L10257.htm. Bibliography Avritzer, L. (2007). Urban Reform, Participation and the Right to the City in Brazil. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies. Bassul, J. R. (2005). Estatuto da Cidade: Quem Ganhou? Quem Perdeu?Brasília: Senado Federal. Caldeira, T., & Holston, J. (2005). “State and Urban Space in Brazil: From Modernist Planning to Democratic Interventions.” In A. Ong & S. J. Collier (Eds.), Global Anthropology: Technology, Governmentality, Ethics. London: Blackwell, pp. 393-416. Carvalho, S. N. d. (2001). “Estatuto da Cidade: Aspectos Políticos e Técnicos do Plano Director.” São Paulo em Perspectiva 15(4): 130-135. Fernandes, E. (2007). “Constructing the ‘Right to the City’ in Brazil.” Social and Legal Studies 16(2): 201-219. Fernandes, E. (2011). “Implementing the Urban Reform Agenda in Brazil: Possibilities, Challenges, and Lessons.” Urban Forum 22(3): 229-314. Filho, J. d. S. C. (2009). Comentários ao Estatuto da Cidade. (3rd Edition ed). Rio de Janeiro: Editora Lumen Juris. Holston, J. (2008). Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) (2010). “Censo Demográfico 2010.” Retrieved October 20, 2011, fromhttp://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/ Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Maricato, E. (1997). “Brasil 2000: Qual Planejamento Urbano?” Cadernos do IPPUR 11(1-2). Maricato, E. (2008). Brasil, Cidades: Alternativas para a Crise Urbana.Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. Maricato, E. (2010). “The Statute of the Peripheral City.” In C. S. Carvalho & A. Rossbach (Eds.), The City Statute of Brazil: A Commentary. São Paulo: Ministry of Cities; Cities Alliance. Mayer, M. (2012). “The ‘Right to the City’ in Urban Social Movements.” In N. Brenner, P. Marcuse & M. Mayer (Eds.), Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. New York: Routledge, pp. 63-85. McCann, E., & Ward, K. (Eds.). (2011). Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2001). “Exporting Workfare/Importing Welfare-to-Work: Exploring the Politics of Third Way Policy Transfer.” Political Geography 20(4): 427-460. Pindell, N. (2006). “Finding a Right to the City: Exploring Property and Community in Brazil and in the United States.” Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 39(2): 435-479. Rolnik, R. (2001). “Territorial Exclusion and Violence: The Case of the State of São Paulo, Brazil.” Geoforum 32(4): 471-482. Santos, M. (2002). A Urbanização Brasileira. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. Souza, M. L. d. (2001). “The Brazilian Way of Conquering the ‘Right to the City’: Successs and Obstacles in the Long Stride Towards an ‘Urban Reform’.” DISP 147(4): 25-31. Souza, M. L. d. (2006). A Prisão e a Ágora: Reflexões em Torno da Democratização do Planejamento e da Gestão das Cidades. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly