|

Originally posted in the Urban Studies Journal blog on May 6, 2021. This blog is on an article in Urban Studies. Click here to access the article. In 2007, Brazil was selected by FIFA as the host country for the 2014 World Cup, which included Rio de Janeiro among the country’s 12 host cities. Two years later, in 2009, the International Olympic Committee announced that Rio would also host the 2016 Olympics. As Brazil prepared to host these major mega-events by fashioning ‘hypermodern’ urban spaces, preparatory developments in Rio’s port area aimed to position the city as a centre of global competition and capitalism. One of its most iconic buildings, the Museum of Tomorrow, shown below, exemplifies this ambition. To do this, urban revitalization projects function as a form of public-private partnership — known in Brazil as operação urbana consorciada — allowing financialization and real estate speculation through relaxed zoning conditions in specific areas, which were ironically allowed through Brazil’s progressive urban legislation, the Statute of the City. Urban revitalization projects often disregard their impact on ethnic minority groups, race relations and the segregatory history of such processes. Even more than the displacement that often results, the link between hypermodernity and race are explicitly produced through mega-event processes. These large-scale developments in Rio came at a cost for the African and Afro-Brazilian communities that existed long before in the area. In this article, we document how Rio’s revitalization of the port area has literally buried the history of the transatlantic slave trade by reframing the narrative through discursive tactics. In Rio’s port area, despite the area’s abandonment and considerable recent challenges, Valongo Wharf is an important landmark as it was the entry point for as many as 900,000 African slaves into Rio. In 2017, UNESCO recognized Valongo as a World Heritage site. The site is part of the African Heritage Circuit promoted through CDURP, the company sponsoring the mega-revitalization project. Conversely, the Cemitério dos Pretos Novos — active from 1769 to 1830 in the area known as “Little Africa” — was a mass grave cemetery for enslaved Africans who died upon arrival. Discovered in 1996, it took years for the site to be officially recognized. This most significant archeological and historical site receives much less attention and resources. While CDURP invested three quarters of its cultural budget in the Museum of Tomorrow and the Rio Art Museum, the Institute to preserve the cemetery received minimum support, struggling to keep its doors open. The multiple contradictions produced through the dualisms we document in Porto Maravilha prompted us to identify the need for a special form of participation that we term legacy participation, which is distinct from participatory planning. Legacy participation highlights the need for Afro-Brazilian decision-making power through jurisdictional authority. We borrow such ideas from indigenous land rights literature, and argue that such forms of devolution could — and should — apply to the context of territorialized African heritage, such as the case of Porto Maravilha. Museum of Tomorrow (Museu do Amanhã). Source: By Domínio Público - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45719417 A slave market in Rio de Janeiro, by Edward Francis Finden, 1824

Source: http://usslave.blogspot.it/2011/08/slave-market-at-rio.html

0 Comments

Originally posted at The Social Policy Blog on April 23, 2020.

This blog is based on an article in Social Policy and Society. Click here to access the article. Recently, Brazil has been in the news due to raging fires in the Amazon, an economic crisis over the past couple of years, and a move to the radical right. Another story, which I focus on in my research, features a narrative of a country emerging from twenty years of dictatorship, and a rights-based urban reform movement in the lead up to the approval of a ‘citizens’ Constitution in 1988. The reform movement also led to the approval of another law, known as the Statute of the City (Estatuto da Cidade) in 2001, which provided tools for cities to plan in a more just way. This approach is inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s idea of the right to the city, or the right to participate in urban life. Despite considerable work on these urban transformations in Brazil, in this article I take this argument one step further. I show that Brazil’s urban transformations and right to the city debate should be seen through perspectives on social citizenship, property rights, and the insurgent planning of Brazil’s urban social movements. This article is primarily reflective and based on my work on Brazilian cities, urban governance, and the right to the city. It was written as a commentary for a special issue on Property and Social Citizenship in Social Policy and Society. Brazil’s experience provides important lessons for how to institutionalise a radical, rights-based urban movement, despite obstacles over the past couple of years. Any understanding of Brazil’s urban experience inevitably begins with the work of French philosopher Henri Lefebvre on the right to the city, whose visits to Brazil left long-lasting effects on the social movements between the 1960s and 1980s, and later on academics, planners, and activists—both in Brazil and globally. For Lefebvre, the right to the city was both a process and struggle in the realm of everyday life. Lefebvre referred to a range of rights, but especially to the right to habitation and the right to participate that, combined, considerably informed Brazil’s urban reform movement. Another important right was the right to difference; cities were places where different people with diverse ideas came together to decide on what their city will look like. As I show in this article, Brazil’s urban experience resonates with T.H. Marshall’s work on the social elements of citizenship. Marshall argued that citizenship involves civil, political and social elements. The social element comprises a range of rights including economic welfare, security, and the right to fully take part in society. Social rights in Brazil have often been exclusionary given the history of inequality and poverty. Yet since the return to political liberalisation, by the 1970s social movements in Brazil’s urban peripheries were asserting a ‘right to have rights’ as a claim against the dictatorship. These urban social movements were integral in reframing citizenship as a more egalitarian framework for social relations, advancing a discourse that formulated needs as social rights. This rights-based dimension was integral in the 1988 Constitution through mechanisms of popular democracy and the recognition of the right to the city as a collective right. Social obligations within property rights — known as the social function of property, or the obligation of land uses that contribute to the common good — have also played a key role in Brazil. Such ideas entered force as far back as the 1930s. More than 50 years later, the 1988 Constitution recognised that private property has a social function, and detailed what achieving the social function would entail. This included a range of tools to promote the social function in practice. Cities larger than 20,000 residents would be responsible for elaborating an approach to achieve the social function through their master plans, and other urban and environmental laws. Thirteen years following the approval of the Constitution, the 2001 Statute of the City clarified how the social function could be applied through tools at the local level. While the Constitution had only included two articles on urban policy, the Statute much more fully detailed these provisions. The goal of urban policy overall, according to the Statute, is to realise the social function of property. Related to the rights-based approach of the urban movements and the importance of property rights for urban reform, insurgent planning has been central idea for Brazil’s urban transformations. Inspired by James Holston’s work on insurgent citizenship, insurgent planning refers to practices and narratives that disrupt the normalised order, offering evidence of citizens’ efforts to resist urban problems. These forms of insurgent planning operate both within planning processes as well as outside the formal sector. In Brazil, insurgent planning can be used to understand how residents defend their rights to land and property to contest disputes over ownership through tactics of resistance and appropriation to claim urban land and services. This article views Brazil’s urban transformations though debates on social citizenship, property rights and insurgent planning. Thus, as planners, accounting for rights also requires responding to issues related property. This perspective on social citizenship highlights the struggles waged in cities over social rights and those already achieved through legislation, in addition to insurgent practices used by social movements. Admittedly, despite many of the achievements since the 1970s, Brazil is still on a long and uncertain road given the recent economic and political upheaval, a history of deep paradoxes, and enduring urban contradictions. In contrast to these recurring paradoxes, in this article, I highlight a perspective that also offers the hope of a solution, providing a window in which to view the transformational nature of Brazil’s urban problems. But successfully formulating these policies depends on the view of federalism followed in any particular country.

Originally posted at Citiscope on May 8, 2017. Both in the lead-up to and following on the heels of October's Habitat III conference on sustainable cities, there has been a renewed interest around the world in promoting national urban policies. This interest stems from an increasing recognition of the importance of such policies for multiple purposes at multiple levels of government. These include, for instance, long-term strategic planning by central governments and their role in financing infrastructure. But they also include attempts to fight poverty, inequality and climate change, as well as to facilitate policy coordination among ministries or agencies. As OECD Secretary-General Ángel Gurría put it during a Habitat III side event, national urban policy “provides a framework so governments and other stakeholders can ‘get cities right.’” Still, what exactly constitutes that framework remains open. The United Nations’ lead agency on urban issues defines a national urban policy as “a coherent set of decisions derived through a deliberate government-led process of coordinating and rallying various actors for a common vision and goal that will promote more transformative, productive, inclusive and resilient urban development for the long term.” But beyond this neat definition is a recognition of the diversity of national institutional arrangements and the challenge of figuring out how to actually implement a national urban policy without offering a one-size-fits-all approach — something that proponents have clearly been keen to steer around. [See: Since Habitat III, an uptick in interest around national urban policies] As momentum picks up for the elaboration and implementation of national urban policies in various countries, the question is increasingly arising: Can federal systems, too, adopt such a framework? Certainly a federal system could make formulating a national urban policy more complex, simply because such policies often involve three or more levels of government. Likewise, well-established state, provincial or municipal capabilities could complicate the formulation of a national urban policy even further. So is a national urban policy possible under a federal system? As it turns out, such policies and federalism are, in fact, compatible. But formulating these policies successfully within such a context depends on the view of federalism followed in any particular country. Key examples Despite the apparent challenges to a federal role in cities within specific national contexts, multiple examples show that a federal system doesn’t preclude a national urban policy. In Australia, for instance, national urban policy seems to have succeeded under a federal system. Within a country that is demographically 90 percent urban, few policies are not de facto urban policies. So with the appointment of a federal minister for cities and the built environment in 2015, commentators asked: Does the federal government finally ‘get’ cities? [See: Six months after Habitat III, is the New Urban Agenda gaining political traction?] The question had a long backstory. Following a failed 2011 attempt to institute a national urban policy and years of federal disengagement in cities, the Australian government inaugurated a Smart Cities Plan in 2016, formulated around investment, policy and technology. The policy is based on metropolitan strategic planning, infrastructure funding and on the British “City Deals” approach, bringing together all levels of government to “deliver better outcomes through a coordinated investment plan for our cities”. In the City Deals approach, introduced in the United Kingdom in 2012, the national government works directly with large cities through individual arrangements, reflecting the unique needs of each city by devolving powers and financial tools, and strengthening local governance. While the Australian approach is interesting, it is just over a year old. For now, the test — and lesson for other countries — is whether it will survive a change in government. Brazil, on the other hand, is a decentralized federal system that is unusual in its recognition of the importance of cities. In 2001, a law known as the Statute of the City (Estatuto da Cidade) was approved, setting out the rights and obligations of cities in the Brazilian federation. The government also created the Ministry of Cities, a federal institution to deal with matters related to urban development and a long-standing demand by the urban reform movements. Since 2003, the ministry has helped Brazil’s numerous municipalities implement the Statute’s directives and acted as a national voice for cities. Another example is Belgium, which is also highly urbanized. Dating from 1999, the country’s national urban policy — the Big City Policy (Politique des Grandes Villes) — supports Belgian cities most affected by deprived neighbourhoods through contracts between the central government and individual cities. These contracts include horizontal coordination between federal sectors and vertical coordination between other stakeholders (at the European, national, regional, local and neighbourhood level). In 2001, the Belgian authorities created the Urban Policy Service to implement the national urban policy. Belgium’s regions also have their own regional urban policies. [See: Can the New Urban Agenda heal India’s urban-rural divide?] Other examples of federal countries with national urban policies include Germany, Mexico and Switzerland. Contentious proposition Despite these positive examples, scepticism continues to flourish over the prospect of a national urban policy being instituted in a federal system. One of the major arguments against this idea rests on a conceptual view of federalism that imagines a constitutional impediment to such policies. Another barrier could be simply that while federal urban policy is possible, it's unnecessary. An alternative viewpoint, however, comes from a more pragmatic approach. This stance makes the case that a federal government can play a substantial role in urban policy if it is prepared to mobilize the fiscal and policy levers at its disposal, in addition to the political consequences of doing so. This pragmatic approach — in contrast to a more theoretical position — was raised in the 1970s by urban scholar Patrick Troy (in reference to the Australian case). [See: Joan Clos: New Urban Agenda ideas ‘are now trickling down’] Here, Canada provides an instructive example. In the 1970s, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau created the Ministry of State for Urban Affairs, establishing a federal urban policy. But that move came about only after a change of mind from the Trudeau, who initially took a more cautious approach to federalism: At first, the prime minister saw any deviation from the constitutional roles of the provinces as a possible cause of friction and instability. This interest in Canada began in earnest in the 1960s, considered a watershed in federal-municipal relations. But in fact, discussion over national urban policy in Canada has come up time and again. Multiple federal governments have attempted to institute such a policy, although each initiative eventually has fizzled away. Over the years, one argument often cited in this perennial discussion has to do with Canada’s unique federal system. As “creatures of the provinces”, Canada’s cities can be formed, dissolved, amalgamated or otherwise altered and their power expanded or restricted only by provincial governments. As a result, Ottawa cannot stoke provincial resentment — particularly from Quebec — about jurisdictional intrusions. Instead, the federal government must seek to enhance federal policy capacity and visibility in Canada’s cities, the country’s key locales of economic, social and cultural interaction. Given significant pressure from the opposition, Trudeau’s move created the most successful foray into national urban policy in Canada thus far. However, such efforts collapsed among intergovernmental tensions — thus highlighting the need for consensus among the collective stakeholders involved in crafting national urban policies in federations. [See: After Habitat III, we need to institutionalize our urban policy dialogues] A similar discussion has taken place in Australia, also a highly federalized country. Despite Australia being a truly urban nation, politicians, scholars and jurists have argued that the federal government has no authority to intervene in urban affairs. As in Canada, several short-lived advances over the years — such as key urban and housing development initiatives in 1972, when both the Labour and left-wing parties agreed to create a cities portfolio within the Commonwealth ministry — have made the case for a federal presence in urban issues. In the United States, there is no national urban policy per se, although there certainly has been interest in the issue. Nonetheless, the federal government had been largely removed from national urban policy since the 1960s. That said, easing the approach to federalism actually has allowed for some steps toward an urban policy. Following years of disengagement in urban affairs, President Barack Obama renewed a federal role in city life, driven by an approach that officials called a “new wave of federalism”. In 2009, the White House launched an Office of Urban Affairs to mobilize federal resources in a coordinated fashion toward cities and to collaborate with local communities through sustainable investments. [See: Why are U. S. mayors missing Habitat III?] While the Obama-era programmes did not amount to a national urban policy, the change in orientation was unquestionable — although it now appears that the Trump administration is dismantling these advances. Flexibility and consensus-buildingDespite the uncertain situation of the United States, interest in national urban policy is clearly rising. Importantly, this growing attention is being accompanied by a strengthening body of international guidance on the issue. Before Habitat III, for instance, UN-Habitat and Cities Alliance published a global overview of national urban policies, while the OECD published a compendium detailing European efforts toward such policies. Both studies highlighted the diversity of national experiences, including those with federal systems. The policy paper on national urban policy prepared for Habitat III likewise recommends flexibility in the institutional form of such policies. [See: Habitat III struggled to deliver — but nonetheless, a new global urban agenda is upon us] By the same token, considering how consensus can be forged around the need for a national urban policy would greatly facilitate this process. Germany’s national urban policy, launched in 2007, is a notable example of such consensus-building. There, prior consensus-building allowed the national urban policy to more easily fit within the complex federal context and to encourage power-sharing among members of the federation. How did Germany approach this process? To build consensus and support for the policy through engagement of a broad range of stakeholders, Germany authorities created a National Urban Development policy board. This body included representatives of a broad range of stakeholders including all levels of government, architects, planners, engineers, chambers of commerce, property owners, tenants, craft associations, the construction industry, retailers, civil society groups and academics. This example is instructive for other countries heading down a similar path. There is also a global initiative already underway that deserves attention: the National Urban Policy Programme of the OECD, UN-Habitat and Cities Alliance. This is a global knowledge-sharing platform on national urban policies and best practices aimed at supporting capacity development. Given the buzz over national urban policy since Habitat III, the time is ripe to demystify the advent of these policies in the context of federal systems. Originally posted in Panoramas.

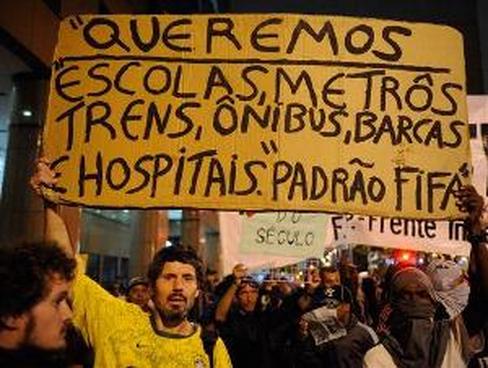

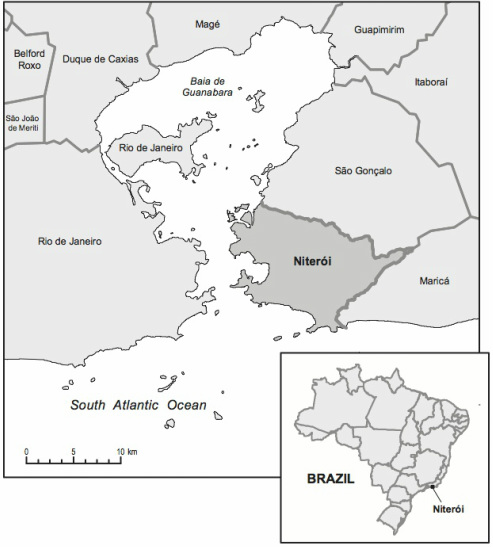

Protest movements in response to a range of issues have been in the spotlight in Brazil over the past three years, prompting considerable discussion about the future of collective action for the country. Drawing on research that occurred before the large-scale 2013 mobilizations occurred, this article in Latin American Research Review attempts to make sense of a perceived decline in social movement activity in urban centres in Brazil, arguing that such alterations result from a changing political context. It attempts to make sense of the many waves of civil society activity in the urban context, based on the idea of a cycle of protests (Tarrow, 1994). Brazil is a particular case where urban social movement activity has been much less significant in recent years than the social movements that emerged in the countryside such as the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), a phenomenon that Souza (2016) has discussed recently. The 2013 protests were the first massive protests in Brazilian cities since at least the Diretas Já movement in 1983-84 (the campaign for direct elections that ended 20 years of military rule). The article focuses on Niterói, a city of about a half-million people across the bay from Rio de Janeiro. Although civil society flourished until the 1990s in Niterói, many interviewees noted that the dynamism that had previously existed in the city was no longer present. Some referred to passivity, others mentioned retracted participation, while others talked about the movements’ “decay.” Given the need for a vibrant civil society in taking forward the goals of the urban reform movement in Brazil, this concern prompted an exploration to more analytically describe the nature of this decay. The urban reform movement, discussed in this article, initiated in the 1980s and composed of popular movements, neighborhood associations, NGOs, trade unions and professional organizations, helped to formulate a proposal for urban reform in the National Constituent Assembly. Ultimately, the movement was integral in helping to approve the Statute of the City in 2001, the national law that provides planning tools for cities based on a social justice approach. As a result, part of this interest in social movements stemmed from a contention of the important role of civil society in both the Brazilian Constitution (1988) building process and in the approval of the Statute of the City. In that sense, this is a very urban story that has played out in Brazil over several decades. This article was written and researched well before Brazilians came out in droves to protest, in part, a gap between theory and practice in June 2013. The June 2013 protests erupted in São Paulo against rising bus fares and were followed by similar protests across Brazil, highlighting the urban nature of the protests (Friendly, 2016). Since writing this article, much has changed in the world of urban social movements in Brazil as well as the political context. As the world watched Brazil prepare for and host the Rio Olympic Games, the economy slumped alongside an ongoing corruption crisis that resulted in, among other things, President Dilma Rousseff being removed from office. In addition to the protests that began in June 2013 to oppose rising bus fares, Brazilians have continued going to the streets to oppose rising transportation costs, corruption, the right to the city in general and the poor economic situation. Following Rousseff’s impeachment, protesters haven’t let up against Michel Temer’s interim government. One of the interesting things that has emerged in all of these events is that the protests at various points in time have come from both the political right and left. These events highlight a key conclusion of the article: that civil society changes and adapts based on the political context, including external opportunities. This approach connects the emergence and decline of protest cycles with political, institutional and cultural changes as key elements in understanding these changing dynamics. Given all the changes that have taken place over the past couple of years in Brazil, it is indeed a key moment for the country, but it is unlikely that civil society in Brazil will be as complacent as perceived in the case of Niterói. There is no question that civil society is playing a key role, but as this paper has argued, the political situation has also changed, redrawing a central element to these shifting dynamics. References Friendly, Abigail 2016 “Urban Policy, Social Movements and the Right to the City in Brazil.” Latin American Perspectives doi: 0094582X16675572. Souza, Marcel Lopes de 2016 “Social Movements in Brazil in Urban and Rural Contexts: Potentials, Limits and “Paradoxes.” In The Political System of Brazil, edited by D. de la Fontaine and T. Stehnken, 229-252. New York: Springer. Tarrow, Sidney 1994 Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Friendly, Abigail. 2016. “The Changing Landscape of Civil Society in Niterói, Brazil.” Latin American Research Review51(1): 218-241. DOI: 10.1353/lar.2016.0012 Questioning the mega-event legacy: Planning and unkept promises in Brazil's world cup of 20146/26/2014 Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com As the opening of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil unfolds, protests have once again raged against the excessive spending on the sports event rather than on much-needed public sector services. In part, the huge funds spent on the World Cup helped to fuel the June 2013 protests across Brazil, among other issues.1 On June 15, 2014, protesters demonstrated in Rio with the slogan ‘se não tiver direitos, não vai ter Copa’ (If there are no rights, there won’t be a World Cup) (see Figure 1). Unkept promises As a backdrop to the protests that started in June 2013 and more recently surrounding the World Cup, a developing story in the planning context is the promise by the Brazilian government to deliver infrastructure to support the World Cup and the disappointing result of unkept promises. This disconnect between promised public infrastructure projects – such as various public transport systems – and the many delayed or yet-to-be started projects, is an intriguing story for planners watching the World Cup develop. This is referred to by Thornley (2012: 207) as the “dark side” of legacy, including the displacement of uses, rights and residents to make way for venues as well as the lost projects from which funds are ultimately diverted. For example, in the Brazilian amazonian city of Manaus, an urban transport system that included a monorail and a BRT was promised yet the project never began. Manaus’ airport is also being upgraded, but was not ready in time for beginning of the World Cup. Many of the longer-term investments in public transportation have also been scrapped, such as the high speed train linking Rio and São Paulo. Projected to begin for the World Cup, the train will only be finished by 2020, if at all. There has also been criticism of the stadiums that will be used only a handful of times for World Cup matches yet will be unlikely to host a team once the games are over. In 2010, the government promised a ‘matrix of responsibilities’ in the 12 cities holding World Cup games.2 In addition to the obvious stadiums and urban transport systems such as BRTs, airports, ports and hotels were promised. In 2010, the estimated investment in infrastructure (urban mobility, airports and ports) was US$8 billion [R$17.7 billion] and all projects were to be ready by December 2013. Delays, cost overruns, lawsuits and corruption scandals have put a damper on the World Cup festivities: “At 100 days before the World Cup, reality proves to be quite different from what was projected on paper: only 18% of infrastructure projects were delivered and investment fell to [US$6.5 billion] R$14.7 billion – cut by [US$1.5 billion] R$3 billion” (Marques, 2014). In the updated matrix in September, there were 45 projects listed in the area of urban mobility (10 of these are improvements surrounding the stadiums), 12 in stadiums, 30 in airports and 6 in airports. Brazil has spent about US$ 11 billion (over $25 billion reais) on infrastructure related to the World Cup. A third of this cost went to both building and refashioning stadiums in the 12 host cities. Despite spending so much on the World Cup, Brazil has delivered only a fraction of the projects it promised to undertake, and many of those are unfinished, such as Rio’s international airport. Many such projects are unfinished and others never left the drawing board. The newspaper Folha de São Pauloreported in May 2014 that only 41% of the planned projects had been completed (or 68 out of 167). This includes the completion of 10% of urban transport projects and 49% of airport and port projects. In addition, 88 projects are incomplete or will be left for after the World Cup to be completed and 11 were entirely abandoned. To get this data, Folha “listed and checked the progress of all actions contained in the so-called ‘matrix of responsibilities’” (Folha de São Paulo, 2014). In addition, despite a decrease in investments, the majority of the projects in the 2010 document increased in cost: “in other words, the decrease in the total value occurred principally because of the exclusion of large projects and not because of the cheapening of the works” (Marques, 2014). Even worse, there has been little official information released about the specifics of the unfinished projects and the percentage compared to the total expected in 2010. While the updated matrix of responsibilities is available online, it shows the volume of funds “projected” but not the amount spent on the projects, making it necsesary to turn to media reports to show infrastructure projects that are delayed or not happening. As Ricardo Setti noted recently in column in Veja, by disclosing the amount of money invested without detailing the specifics, the government manufactures a magical account: “Magic makes most projects receive the generic stamp of ‘adequate progress’” (Setti, 2014). Overall, the last priority in the leadup to the World Cup was transportation – after stadiums and airports. The solution for notoriously bad congestion in some cities was to declare holidays for the days with games. In the second week of the games, Rio had only two regular business days. Rio’s much-lauded BRT will only be partly operational for the World Cup, with only some of its 45 stations running. BRTs and light rail projects in other cities have been scrapped. Although the problem is arguably not only related to the World Cup, the promise of many large-scale infrastructure projects such as BRTs is deceptive. The legacy of the games for whom? The legacy of the games is often touted as a rationale for hosting such events, together with legitimizing the spatial transformations of the city. Indeed, the expericence of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics helped to perpetuate the notion of the wider urban legacy of the games while “images of empty venues post-games raised questions about the economic and environmental costs of mega-events and the benefits to local populations” (Brownhill, et al., 2013: 112). The idea that hosting mega-events such as the World Cup will result in few social benefits has been pervasive this time around, as has been the case in past events. As a BBC story noted recently, although Brazil has a duty to put on a good show, “what about the government’s “duty” to its own people?” (Davies, 2014). In a critque of use of the term ‘legacy’ for the city of Rio, Magalhães (2013: 94) notes that its use appears in numersous situations where an explanation of the urban interventions in Rio was deemed necessary through a repertoire of removals, which have resulted in changes in the use of city space and the displacement of some favela residents. For that reason, Brownhill et al (2013) not that such legacies are political, with different possible visions between the initial drawing up of plans and the actual delivery of those plans. Indeed, in contrast to the role such events play as vehicles for development, much of the literature has characterized mega-events as “powerful engines in the neo-liberal reconfiguration of the city, promoting the privatization and commodification of urban space, and the implementation of market-oriented economic policies” (Sánchez & Broudehoux, 2013: 135). In the case of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, Pillay and Bass (2008: 331) note that: Mega-events are often used as ‘spectacles’ that can best be understood as either instruments of hegemonic power, or displays of urban ‘boosterism’ by economic elites wed to a particularly narrow-minded pro-growth vision of the city. As such, these events are often seen as no more than public relations ventures far removed from the realities of urban problems and challenges. Similarly, in reference to the case of Rio (probably the most widely studied city in Brazil in relation to the mega-events because of the coming Olympics in 2016), Sánchez and Broudehoux (2013) argue that mega-events are being instrumentalized by local political and economic elites, creating an exclusive vision of urban regeneration. Ultimately, the authors argue, this has paved the way for state-assisted privatization and commodification of the urban realm, fulfilling the needs of capital while intensifying socio-spatial segregation, inequality and social conflicts. Carlos Vainer (2011) has made the argument that mega-events are part of a process that has led to a city of exception, a new type of urban regime or reconfiguration of power structures at the local and national levels which imposes a new neo-liberal order marked by authoritarianism and exceptionalism: “The mega-events realized in its intense and full form, the city of exception. In this city, everything goes outside the formal institutional mechanisms… The city of mega-events is the city of ad hoc decisions, exemptions, special permits…” Drawing on Agamben’s (2005) idea of a state of exception, such exceptions turn into the rule as they become key tools to bypass the democratic political process in implementing mega projects. In this scheme, the General Law of the World Cup (Lei Geral da Copa) acts as an exemption. During the World Cup, some Brazilian laws have even been temporarily revoked. One of the most noteworthy of these exemptions was to reverse the ban on alcohol in stadiums, allowing Budweiser (a FIFA sponsor) to sell beer at World Cup games.

This discourse about the city of exceptions forces one to think about who the investments are benefitting, even as mega-events are touted as profiting the city as a whole. So what can we expect for the 2016 Olympics? Of course, all eyes will be on Rio as 2016 nears. 1 See my post on the protests in 2013 here. 2 See www.copa2014.gov.br/en/brasilecopa/sobreacopa/matriz-responsabilidades. References Agamben, G. (2005). State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Brownhill, S., Keivani, R., & Pereira, G. (2013). “Olympic Legacies and City Development Strategies in London and Rio; Beyond the Carnival Mask?” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 5(2): 111-131. Davies, W. (2014, June 16). “Has Brazil proved World Cup doubters wrong?” BBC. Folha de São Paulo (2014, May 13). “A 30 Dias da Copa, Metade das Metas Não Foi Cumprida.” Folha de São Paulo. Magalhães, A. (2013). “O ‘Legado” dos Megaeventos Esportivos: A Reatualização da Remoção de Favelas no Rio de Janeiro.” Horizontes Antropológicos 19(40): 89-118. Marques, F. (2014, March 4). “A 100 Dias da Copa, Só 18% das Obras de Infraestrutura Foram Entregues.” O Globo. Pillay, U., & Bass, O. (2008). “Mega-events as a Response to Poverty Reduction: The 2010 FIFA World Cup and its Urban Development Implications.” Urban Forum 19(3): 329-346. Sánchez, F., & Broudehoux, A.-M. (2013). “Mega-Events and Urban Regeneration in Rio de Janeiro: Planning in a State of Emergency.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 5(2): 132-153. Setti, R. (2014, March 7). “VEJAM O RIDÍCULO: O trem-bala São Paulo-Rio, que nem foi licitado — e talvez nunca venha a existir -, consta na papelada do governo como estando ‘com andamento adequado’.” Veja. Thornley, A. (2012). “The London 2012 Olympics: What Legacy?” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 4(2): 206-210. Vainer, C. (2011). Cidade de Exceção: Reflexões a Partir do Rio de Janeiro. Paper presented at the XIV Encontro Nacional da ANPUR, Rio de Janeiro, May 23-27. Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com (Excerpt from “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil” inPlanning Theory & Practice by Abigail Friendly). Although Brazil is notorious for its spatially segregated cities and high levels of inequality, a number of urban policy initiatives have evolved there since the 1990s, providing insights into how cities might improve life for city dwellers. In the wake of a twenty-year dictatorship, social movements in Brazil gained force during the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in a robust urban reform movement. This process of re-democratization led to the promulgation of a new ‘citizens’ Constitution in 1988, which included, for the first time, a specific chapter on urban policy. During this period, Brazil underwent rapid urbanization – its urban population climbed from 44.6% in 1960 to 84.3% in 2010 – alongside growth in social inequality, socio-spatial segregation and unplanned development (IBGE, 2010; Maricato, 2008; Rolnik, 2001; Santos, 2002). It is in this context – post-dictatorship, re-democratization and the forceful Brazilian social movements – that one new Brazilian urban policy has garnered international attention. Throughout the 1990s the urban reform movements maintained momentum, and on July 10, 2001 the Statute of the City was enacted. This formal incorporation of the right to the city into national law is unprecedented and unique, deriving from the concept of French sociologist Henri Lefebvre on the right to the city as a process and a struggle in the realm of every day life and, from the right to the city movement, as a right to participate in the production of urban space (Lefebvre, 1968, 1996; Mayer, 2012). In the Brazilian context, the right to the city means the combination of the principles of the ‘social function of property and of the city’ and the democratic management of cities (Fernandes, 2011). This can be interpreted as a mandate to guarantee the well-being of all city residents and the democratic access to goods and services produced in cities (Bassul, 2005; Filho, 2009). The Statute captures a new model of urban planning and management, a huge change in outlook from the old planning model grounded in modernism that prevailed between the 1940s and 1980s in Brazil, which resulted in a structure of urban inequality and exclusion by governing without generating social equality nor including the population in the process (Caldeira & Holston, 2005; Maricato, 1997). Among international observers, policy makers, academics, planners and activists, there is no question that the Statute is an innovative law from the standpoint of its legal and urban advances (Carvalho, 2001; Fernandes, 2007; Filho, 2009; Pindell, 2006; Souza, 2006). Certainly, the passing of the Statute inspired hope from both observers and participants. It has been called “remarkable in the history of urban legislation, policy, and planning not only in Brazil but worldwide” (Holston, 2008: 292) and an “inspiring example“ of action by national governments (Fernandes, 2007: 212). The literature thus far has focused on the legal and urban implications of the right to the city in Brazil as well as the social movements involved in this process (Avritzer, 2007; Caldeira & Holston, 2005; Fernandes, 2007; Pindell, 2006; Souza, 2001). However, the connection between this landmark right to the city legislation and an analysis of the practical on-the-ground implications of the Statute has not yet been evaluated. This paper includes an overview of what the right to the city means in theory, followed by an exploration of the Brazilian experience in implementing the right to the city. Based on data from my field work in Niterói in the State of Rio de Janeiro (shown in Figure 2), I explore the challenges in the Brazilian planning framework; in particular, the lack of implementation of the Statute of the City. I use the experience of one city, Niterói, to understand the possibilities and challenges involved in implementing the directives of the Statute of the City. The goal of this paper is twofold: first, I argue that the incorporation of the right to the city in a legal framework such as the Statute is unprecedented and unique and thus deserves recognition; second, in reflecting on the poor implementation of the Statute of the City in cities in Brazil, I argue that a more nuanced approach is needed in understanding the changes that have taken place in Brazil’s urban policy and planning over the past twenty years. Viewing the Brazilian urban climate since the period of military dictatorship in the 1980s, the country has come a long way with many advances; among them the Constitution, the Statute of the City and interesting experiences of urban policy in various cities. In that sense this story needs to be viewed as a process at one point along a long road. The approval of the Statute is only the first step. Its adoption on the part of the popular movements and local administrations was no small achievement and much more can be expected to result from this experience in future years. There have been significant changes in Brazil in terms of the role of planning, the production of urban space and the role of the state since the new Constitution. The results have significantly changed the planning model in Brazil to one focused on democratic spaces with “the potential to generate urban spaces that are less segregated and that fulfill their ‘social function’” (Caldeira & Holston, 2005: 411). Thus, Ermínia Maricato (2010: 22), a key policy-maker and academic deeply involved in the development of the Statute, notes that “regardless of the difficulty of implementing the City Statute, we believe that it is nevertheless the harbinger of a new and different future.” This suggests that what is needed is a nuanced approach to understanding the progress of the Statute of the City in Brazil. Combined with utopian Lefebvrian ideals, which do not fully explore how to practically implement the right to the city, such nuance is key.

In this paper I make the case for the unprecedented and unique incorporation of the right to the city as a key part of the fabric of the Statute of the City. Moreover, the role of civil society in pushing for the right to the city as a key component of the Statute is both compelling and educational for planning theory and practice, as it shows that bottom-up movements can produce policy change with the potential to affect the social fabric of urban life. In the paper, I outline some preliminary problems leading to poor implementation of the Statute of the City that emerged from my field work in Niterói. As a positive example of an innovative urban policy tool, both the Statute’s ideal – upholding the right to the city – and the results of its implementation, should be better known within the broader planning community. The Statute of the City captures a model of urban planning and management that is unique, not only in Brazil, but also worldwide. However, the implementation problems do not mean that learning experiences have not emerged from the Brazilian experience. Despite the implementation difficulties, this model of participatory planning may provide useful lessons for designing participatory planning, and it suggests ways in which the right to the city can be guaranteed for all. The planning model in Brazil is, indeed, a framework that could be applied in other locales. Despite contextual variations between countries, the Statute’s principles – based on the right to the city and the social function of property – could be transferred to other contexts with the recognition that policies, as socio-spatial processes, may actually change as they travel (McCann & Ward, 2011; Peck & Theodore, 2001). Despite Brazil’s advances in law, guaranteeing planning and land use, in practice, the lack of implementation has been challenging, as the case of Niterói suggests. This paper explores the right to the city in theory and practice, arguing for due recognition of this landmark legal and urban framework. Although in Brazil it has become common to argue that the Statute is still too recent to evaluate and address the clear problems in its implementation, criticism and discussion regarding the practical applications of the Statute are healthy and needed components of the debate in order to improve the practice of the right to the city. While the euphoria that surrounded the Statute during the 1990s no longer exists in Brazil, the climate is ripe for a new discussion about how to move beyond and to make the Statute of the City truly effective. Overall, the experience of applying the right to the city in Brazil takes the theoretical (and inherently utopian) concept as Lefebvre conceived it, forward, pointing to the challenges of implementing such policies in practice, but also pointing to experiences which could be used to inform planning practice elsewhere. For the full text of the article, “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil” in Planning Theory & Practice, see http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.783098. 1 Known as ‘Estatuto da Cidade,’ or Law No 10.257. Seehttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/LEIS_2001/L10257.htm. Bibliography Avritzer, L. (2007). Urban Reform, Participation and the Right to the City in Brazil. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies. Bassul, J. R. (2005). Estatuto da Cidade: Quem Ganhou? Quem Perdeu?Brasília: Senado Federal. Caldeira, T., & Holston, J. (2005). “State and Urban Space in Brazil: From Modernist Planning to Democratic Interventions.” In A. Ong & S. J. Collier (Eds.), Global Anthropology: Technology, Governmentality, Ethics. London: Blackwell, pp. 393-416. Carvalho, S. N. d. (2001). “Estatuto da Cidade: Aspectos Políticos e Técnicos do Plano Director.” São Paulo em Perspectiva 15(4): 130-135. Fernandes, E. (2007). “Constructing the ‘Right to the City’ in Brazil.” Social and Legal Studies 16(2): 201-219. Fernandes, E. (2011). “Implementing the Urban Reform Agenda in Brazil: Possibilities, Challenges, and Lessons.” Urban Forum 22(3): 229-314. Filho, J. d. S. C. (2009). Comentários ao Estatuto da Cidade. (3rd Edition ed). Rio de Janeiro: Editora Lumen Juris. Holston, J. (2008). Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) (2010). “Censo Demográfico 2010.” Retrieved October 20, 2011, fromhttp://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/ Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Maricato, E. (1997). “Brasil 2000: Qual Planejamento Urbano?” Cadernos do IPPUR 11(1-2). Maricato, E. (2008). Brasil, Cidades: Alternativas para a Crise Urbana.Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. Maricato, E. (2010). “The Statute of the Peripheral City.” In C. S. Carvalho & A. Rossbach (Eds.), The City Statute of Brazil: A Commentary. São Paulo: Ministry of Cities; Cities Alliance. Mayer, M. (2012). “The ‘Right to the City’ in Urban Social Movements.” In N. Brenner, P. Marcuse & M. Mayer (Eds.), Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. New York: Routledge, pp. 63-85. McCann, E., & Ward, K. (Eds.). (2011). Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2001). “Exporting Workfare/Importing Welfare-to-Work: Exploring the Politics of Third Way Policy Transfer.” Political Geography 20(4): 427-460. Pindell, N. (2006). “Finding a Right to the City: Exploring Property and Community in Brazil and in the United States.” Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 39(2): 435-479. Rolnik, R. (2001). “Territorial Exclusion and Violence: The Case of the State of São Paulo, Brazil.” Geoforum 32(4): 471-482. Santos, M. (2002). A Urbanização Brasileira. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. Souza, M. L. d. (2001). “The Brazilian Way of Conquering the ‘Right to the City’: Successs and Obstacles in the Long Stride Towards an ‘Urban Reform’.” DISP 147(4): 25-31. Souza, M. L. d. (2006). A Prisão e a Ágora: Reflexões em Torno da Democratização do Planejamento e da Gestão das Cidades. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil. Brazilian protests in the planning context: How can we narrow the gap between theory and practice?11/8/2013 Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com Recently the very real challenges of life in Brazilian cities became evident to international audiences as Brazilians took to the streets in full force to protest poor delivery of public services, widespread mismanagement of government funds and general dissatisfaction with the status quo of political representation.Starting in June 2013, the demonstrations were sparked by an increase in bus fares in São Paulo, but quickly spread throughout the country denouncing a host of problems that plague Brazilian cities including violence, inadequate sanitation and housing, and a slow daily commute in crowded, often dangerous and consistently unreliable transportation. As the protests expanded to other Brazilian cities, the complexity of the issues raised by the protesters became visible to observers (Castilho, 2003). These protests basically centre on two questions: what type of city is lived in the present and what is desired for city life in the future. The protests also stand for demands for the right to the city: “the right to mobility … is also the right to the city, to collective decision-making, to opportunity, to justice” (Williamson, 2013). In addition, the demonstrations revolve around questions of democracy. As the urbanist Raquel Rolnik (Rolnik, 2013b) observed in a blog post, “the desire to participate also seemed very visible. People want to be consulted, they want their views to be taken into account. Representative democracy in Brazil is clearly experiencing a crisis.” The Brazilian protesters were moved by a latent impulse to change public services, including transportation, education and health, but ultimately to transform Brazilian society and how political power is used. As a result, the protests are anti-status quo (Vainer, 2013). As the demonstrations mushroomed, they transformed into a movement against bad politics, a persistent malady of Brazilian society throughout its history. The people’s challenge is not against a particular political party, but against all those in power. In fact, political party flags were banned from many of the protests on the streets. For observers, what brought the movements together in part was a push against the dominance of the ruling political powers such as those in charge of organizing and funding mega-events like the World Cup, the media and large corporations. Although protests took place in dozens of metropolitan areas across Brazil, the biggest demonstrations were in Rio, where the most drastic results of misspending in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics have occurred at the same time as some of the city’s low income groups are being displaced in favour of questionable infrastructure improvements and over-budget sports venues. The rise of these movements emerged in the context of the mega-events, which have been perceived as having channeled resources to the benefit of powerful political and economic actors. Therefore, the protests demonstrate a collective cry out against entrenched private interests in Brazil, such as the private bus operators, taking advantage of the established order at the expense of the majority of the population who have gotten the raw end of the deal in public services. The Free Pass Movement (Movimento Passe Livre), a movement against increased fares in mass transit, noted that: “Like a ghost that haunts cities leaving marks on the living space and memory, the popular uprisings around transportation assail the history of Brazilian metropolises since their formation … [The movements] are a worthy expression of rage against a system completely delivered to the logic of the commodity” (Movimento Passe Livre, 2013). As the protests quickly snowballed across Brazil, they underscored a change from a less obvert, more complacent public. Yet observers of Brazil’s urban situation knew that fragmented demonstrations, dissatisfaction and resistance movements had been spreading in urban areas (Maricato, 2013; Vainer, 2013).

For Carlos Vainer (2013), a renowned economist and sociologist, the spark that ignited the protests was the well-known adverse conditions in Brazilian cities. Similarly, long-time urbanist Ermínia Maricato (2013) argued that the main objectives of the protests and the conditions of Brazilian cities are inherently connected. Despite promises to transform this situation by recent progressive governments, decades of stagnation have affected Brazil’s cities and poor urban dwellers have experienced the worst consequences. Exacerbating this situation, the adoption of neoliberal ideals throughout the ‘90s has had serious repercussions in Brazilian cities. Neoliberalism “deepened and sharpened the known problems” inherited by “forty years of exclusionary developmentalism: favelization, informal, precarious or nonexistent services, deep inequalities, environmental degradation, urban violence, congestion and rising costs of public transport and urban segregation” (Vainer, 2013, section 3.3). As a result, the evident contradictions of the system gave rise to resistance movements that aim to overhaul the status quo in Brazilian cities. Following the first protests in São Paulo, President Dilma Rousseff announced that the government had heard the “voices for change” which gave “a direct message” to society standing for citizenship, education, health, high quality transportation and the right to participate: “This direct message from the streets stands for the right to influence in decisions at all government, legislature, and judicial levels” (Mendes, 2013). Still, the governments’ commitment to tackle the protesters’ demands have been challenged. The protests represent forgotten promises, “the resumption of important claims of struggle for basic social rights” and also “a sign that Brazilian society is very happy to have more money to buy more things, but that is not enough” (Rolnik, 2013b). The largest protests in Brazil in almost 20 years, the 2013 movements share similar ideals with the urban reform movements of the 1970s and 1980s. These movements questioned urban conditions in Brazilian cities, calling for urban reform based on the idea of the right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968). The urban social movements of the 1970s and 1980s helped to bring urban issues to centre stage, culminating in the massive demonstrations that led to the transition from military rule into a new democratic Constitution for the country in 1988. They also played a key role in the approval of the 2001 Statute of the City, an important Brazilian law that formally embraces the right to the city for all through participatory planning and attempts to improve life for city dwellers through planning based on ideals of social justice (Avritzer, 2010). Although the 2013 protests were a surprise to international audiences, like the earlier urban reform movements, they question urban conditions and demonstrate a clear dissatisfaction among many Brazilians with the wide separation between theory and practice in Brazil (Maricato, 2011). After 25 years of a return to democracy, political commitments to make progress on corruption, poor governance and the misuse of public spending have not been realized through tangible results. Frustrated by the public promises yet to be fulfilled, more than a million Brazilians came out in full force, demonstrating that this gap between theory and practice needs to be remedied. Beyond the general disparity between theory and practice, in the planning context this gap is even more readily evident and its nefarious results affect every aspect of the lives of urban dwellers daily. Indeed, the ideals of the urban reform movements have not resulted in real gains in addressing the myriad of difficulties of Brazilian urban life; the urban reform agenda has been left behind. And despite widespread praise of progressive legislation in Brazil such as the Statute of the City, the results have been discouraging, as I have described in the case of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro State (Friendly, 2013) and others have shown in other cities (Santana, 2011). For example, the application of public participation has been challenging while the implementation of planning tools that could put socially justice planning into use have been partial, at best. As a result, a gap between the original goals of the urban reform movement and local practice has become unmistakeable in Brazilian planning practice. The protests that emerged in June 2013 challenge not only particular planning issues including transportation, but also the poor application of proposals such as those made by the urban reform movements. As a result, these protests should be regarded as evidence of the fact that in Brazil’s cities, where the overwhelming majority of Brazilians live, conditions have not improved and tangible results have not been reached despite promises to achieve the right to the city for all. Bibliography Avritzer, L. (2010). “Democratizing Urban Policy in Brazil: Participation and the Right to the City.” In J. Gaventa & R. McGee (Eds.), Citizen Action and National Policy Reform: Making Change Happen. London: Zed Books, pp. 153-173. Castilho, C. (2013, June 25). “O Desafio da Complexidade na Crise das Manifestações de Rua.” Observatório da Imprensa Retrieved July 2, 2013, fromhttp://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/posts/view/o_desafio_da_complexidade_na_crise_das_manifestacoes_de_rua Friendly, A. (2013). “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil.” Planning Theory and Practice 14(2): 158-179. Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. Maricato, E. (2011). O Impasse da Política Urbana no Brasil. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes. Maricato, E. (2013). “É a Questão Urbana, Estúpido!”. In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Mendes, P. (2013, June 18). “Dilma Defende Protestos e Diz que Governo Ouve ‘Vozes pela Mudança’.” O Globo. Movimento Passe Livre (2013). “Não Começou em Salvador, Não Vai Terminar em São Paulo.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Rolnik, R. (2013a). “Apresentação: As Vozes das Ruas: As Revoltas de Junho e suas Interpretações.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Rolnik, R. (2013b) “São Paulo: A Voz das Ruas e a Oportunidade de Mudanças.” Blog da Raquel Rolnik. Accessed on July 4, 2013 at http://raquelrolnik.wordpress.com/2013/06/18/sao-paulo-a-voz-das-ruas-e-a-oportunidade-de-mudancas. Santana, C. R. S. (2011). Aplicação do Estatuto da Cidade em Salvador no Século XXI: Discurso e a Prática. Unpublished Masters, Universidade Salvador, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento Regional e Urbano, Salvador. Vainer, C. (2013). “Quando a Cidade vai às Ruas.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Williamson, T. (2013, June 19). “It’s Just the Beginning; Change Will Come.” The New York Times. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly