|

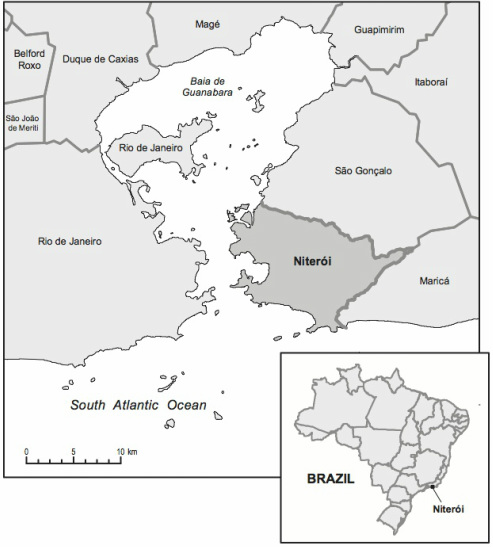

Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com (Excerpt from “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil” inPlanning Theory & Practice by Abigail Friendly). Although Brazil is notorious for its spatially segregated cities and high levels of inequality, a number of urban policy initiatives have evolved there since the 1990s, providing insights into how cities might improve life for city dwellers. In the wake of a twenty-year dictatorship, social movements in Brazil gained force during the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in a robust urban reform movement. This process of re-democratization led to the promulgation of a new ‘citizens’ Constitution in 1988, which included, for the first time, a specific chapter on urban policy. During this period, Brazil underwent rapid urbanization – its urban population climbed from 44.6% in 1960 to 84.3% in 2010 – alongside growth in social inequality, socio-spatial segregation and unplanned development (IBGE, 2010; Maricato, 2008; Rolnik, 2001; Santos, 2002). It is in this context – post-dictatorship, re-democratization and the forceful Brazilian social movements – that one new Brazilian urban policy has garnered international attention. Throughout the 1990s the urban reform movements maintained momentum, and on July 10, 2001 the Statute of the City was enacted. This formal incorporation of the right to the city into national law is unprecedented and unique, deriving from the concept of French sociologist Henri Lefebvre on the right to the city as a process and a struggle in the realm of every day life and, from the right to the city movement, as a right to participate in the production of urban space (Lefebvre, 1968, 1996; Mayer, 2012). In the Brazilian context, the right to the city means the combination of the principles of the ‘social function of property and of the city’ and the democratic management of cities (Fernandes, 2011). This can be interpreted as a mandate to guarantee the well-being of all city residents and the democratic access to goods and services produced in cities (Bassul, 2005; Filho, 2009). The Statute captures a new model of urban planning and management, a huge change in outlook from the old planning model grounded in modernism that prevailed between the 1940s and 1980s in Brazil, which resulted in a structure of urban inequality and exclusion by governing without generating social equality nor including the population in the process (Caldeira & Holston, 2005; Maricato, 1997). Among international observers, policy makers, academics, planners and activists, there is no question that the Statute is an innovative law from the standpoint of its legal and urban advances (Carvalho, 2001; Fernandes, 2007; Filho, 2009; Pindell, 2006; Souza, 2006). Certainly, the passing of the Statute inspired hope from both observers and participants. It has been called “remarkable in the history of urban legislation, policy, and planning not only in Brazil but worldwide” (Holston, 2008: 292) and an “inspiring example“ of action by national governments (Fernandes, 2007: 212). The literature thus far has focused on the legal and urban implications of the right to the city in Brazil as well as the social movements involved in this process (Avritzer, 2007; Caldeira & Holston, 2005; Fernandes, 2007; Pindell, 2006; Souza, 2001). However, the connection between this landmark right to the city legislation and an analysis of the practical on-the-ground implications of the Statute has not yet been evaluated. This paper includes an overview of what the right to the city means in theory, followed by an exploration of the Brazilian experience in implementing the right to the city. Based on data from my field work in Niterói in the State of Rio de Janeiro (shown in Figure 2), I explore the challenges in the Brazilian planning framework; in particular, the lack of implementation of the Statute of the City. I use the experience of one city, Niterói, to understand the possibilities and challenges involved in implementing the directives of the Statute of the City. The goal of this paper is twofold: first, I argue that the incorporation of the right to the city in a legal framework such as the Statute is unprecedented and unique and thus deserves recognition; second, in reflecting on the poor implementation of the Statute of the City in cities in Brazil, I argue that a more nuanced approach is needed in understanding the changes that have taken place in Brazil’s urban policy and planning over the past twenty years. Viewing the Brazilian urban climate since the period of military dictatorship in the 1980s, the country has come a long way with many advances; among them the Constitution, the Statute of the City and interesting experiences of urban policy in various cities. In that sense this story needs to be viewed as a process at one point along a long road. The approval of the Statute is only the first step. Its adoption on the part of the popular movements and local administrations was no small achievement and much more can be expected to result from this experience in future years. There have been significant changes in Brazil in terms of the role of planning, the production of urban space and the role of the state since the new Constitution. The results have significantly changed the planning model in Brazil to one focused on democratic spaces with “the potential to generate urban spaces that are less segregated and that fulfill their ‘social function’” (Caldeira & Holston, 2005: 411). Thus, Ermínia Maricato (2010: 22), a key policy-maker and academic deeply involved in the development of the Statute, notes that “regardless of the difficulty of implementing the City Statute, we believe that it is nevertheless the harbinger of a new and different future.” This suggests that what is needed is a nuanced approach to understanding the progress of the Statute of the City in Brazil. Combined with utopian Lefebvrian ideals, which do not fully explore how to practically implement the right to the city, such nuance is key.

In this paper I make the case for the unprecedented and unique incorporation of the right to the city as a key part of the fabric of the Statute of the City. Moreover, the role of civil society in pushing for the right to the city as a key component of the Statute is both compelling and educational for planning theory and practice, as it shows that bottom-up movements can produce policy change with the potential to affect the social fabric of urban life. In the paper, I outline some preliminary problems leading to poor implementation of the Statute of the City that emerged from my field work in Niterói. As a positive example of an innovative urban policy tool, both the Statute’s ideal – upholding the right to the city – and the results of its implementation, should be better known within the broader planning community. The Statute of the City captures a model of urban planning and management that is unique, not only in Brazil, but also worldwide. However, the implementation problems do not mean that learning experiences have not emerged from the Brazilian experience. Despite the implementation difficulties, this model of participatory planning may provide useful lessons for designing participatory planning, and it suggests ways in which the right to the city can be guaranteed for all. The planning model in Brazil is, indeed, a framework that could be applied in other locales. Despite contextual variations between countries, the Statute’s principles – based on the right to the city and the social function of property – could be transferred to other contexts with the recognition that policies, as socio-spatial processes, may actually change as they travel (McCann & Ward, 2011; Peck & Theodore, 2001). Despite Brazil’s advances in law, guaranteeing planning and land use, in practice, the lack of implementation has been challenging, as the case of Niterói suggests. This paper explores the right to the city in theory and practice, arguing for due recognition of this landmark legal and urban framework. Although in Brazil it has become common to argue that the Statute is still too recent to evaluate and address the clear problems in its implementation, criticism and discussion regarding the practical applications of the Statute are healthy and needed components of the debate in order to improve the practice of the right to the city. While the euphoria that surrounded the Statute during the 1990s no longer exists in Brazil, the climate is ripe for a new discussion about how to move beyond and to make the Statute of the City truly effective. Overall, the experience of applying the right to the city in Brazil takes the theoretical (and inherently utopian) concept as Lefebvre conceived it, forward, pointing to the challenges of implementing such policies in practice, but also pointing to experiences which could be used to inform planning practice elsewhere. For the full text of the article, “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil” in Planning Theory & Practice, see http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.783098. 1 Known as ‘Estatuto da Cidade,’ or Law No 10.257. Seehttp://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/LEIS_2001/L10257.htm. Bibliography Avritzer, L. (2007). Urban Reform, Participation and the Right to the City in Brazil. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies. Bassul, J. R. (2005). Estatuto da Cidade: Quem Ganhou? Quem Perdeu?Brasília: Senado Federal. Caldeira, T., & Holston, J. (2005). “State and Urban Space in Brazil: From Modernist Planning to Democratic Interventions.” In A. Ong & S. J. Collier (Eds.), Global Anthropology: Technology, Governmentality, Ethics. London: Blackwell, pp. 393-416. Carvalho, S. N. d. (2001). “Estatuto da Cidade: Aspectos Políticos e Técnicos do Plano Director.” São Paulo em Perspectiva 15(4): 130-135. Fernandes, E. (2007). “Constructing the ‘Right to the City’ in Brazil.” Social and Legal Studies 16(2): 201-219. Fernandes, E. (2011). “Implementing the Urban Reform Agenda in Brazil: Possibilities, Challenges, and Lessons.” Urban Forum 22(3): 229-314. Filho, J. d. S. C. (2009). Comentários ao Estatuto da Cidade. (3rd Edition ed). Rio de Janeiro: Editora Lumen Juris. Holston, J. (2008). Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística) (2010). “Censo Demográfico 2010.” Retrieved October 20, 2011, fromhttp://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/censo2010/ Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. Maricato, E. (1997). “Brasil 2000: Qual Planejamento Urbano?” Cadernos do IPPUR 11(1-2). Maricato, E. (2008). Brasil, Cidades: Alternativas para a Crise Urbana.Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. Maricato, E. (2010). “The Statute of the Peripheral City.” In C. S. Carvalho & A. Rossbach (Eds.), The City Statute of Brazil: A Commentary. São Paulo: Ministry of Cities; Cities Alliance. Mayer, M. (2012). “The ‘Right to the City’ in Urban Social Movements.” In N. Brenner, P. Marcuse & M. Mayer (Eds.), Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. New York: Routledge, pp. 63-85. McCann, E., & Ward, K. (Eds.). (2011). Mobile Urbanism: Cities and Policymaking in the Global Age. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2001). “Exporting Workfare/Importing Welfare-to-Work: Exploring the Politics of Third Way Policy Transfer.” Political Geography 20(4): 427-460. Pindell, N. (2006). “Finding a Right to the City: Exploring Property and Community in Brazil and in the United States.” Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 39(2): 435-479. Rolnik, R. (2001). “Territorial Exclusion and Violence: The Case of the State of São Paulo, Brazil.” Geoforum 32(4): 471-482. Santos, M. (2002). A Urbanização Brasileira. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. Souza, M. L. d. (2001). “The Brazilian Way of Conquering the ‘Right to the City’: Successs and Obstacles in the Long Stride Towards an ‘Urban Reform’.” DISP 147(4): 25-31. Souza, M. L. d. (2006). A Prisão e a Ágora: Reflexões em Torno da Democratização do Planejamento e da Gestão das Cidades. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil.

1 Comment

Brazilian protests in the planning context: How can we narrow the gap between theory and practice?11/8/2013 Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com Recently the very real challenges of life in Brazilian cities became evident to international audiences as Brazilians took to the streets in full force to protest poor delivery of public services, widespread mismanagement of government funds and general dissatisfaction with the status quo of political representation.Starting in June 2013, the demonstrations were sparked by an increase in bus fares in São Paulo, but quickly spread throughout the country denouncing a host of problems that plague Brazilian cities including violence, inadequate sanitation and housing, and a slow daily commute in crowded, often dangerous and consistently unreliable transportation. As the protests expanded to other Brazilian cities, the complexity of the issues raised by the protesters became visible to observers (Castilho, 2003). These protests basically centre on two questions: what type of city is lived in the present and what is desired for city life in the future. The protests also stand for demands for the right to the city: “the right to mobility … is also the right to the city, to collective decision-making, to opportunity, to justice” (Williamson, 2013). In addition, the demonstrations revolve around questions of democracy. As the urbanist Raquel Rolnik (Rolnik, 2013b) observed in a blog post, “the desire to participate also seemed very visible. People want to be consulted, they want their views to be taken into account. Representative democracy in Brazil is clearly experiencing a crisis.” The Brazilian protesters were moved by a latent impulse to change public services, including transportation, education and health, but ultimately to transform Brazilian society and how political power is used. As a result, the protests are anti-status quo (Vainer, 2013). As the demonstrations mushroomed, they transformed into a movement against bad politics, a persistent malady of Brazilian society throughout its history. The people’s challenge is not against a particular political party, but against all those in power. In fact, political party flags were banned from many of the protests on the streets. For observers, what brought the movements together in part was a push against the dominance of the ruling political powers such as those in charge of organizing and funding mega-events like the World Cup, the media and large corporations. Although protests took place in dozens of metropolitan areas across Brazil, the biggest demonstrations were in Rio, where the most drastic results of misspending in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics have occurred at the same time as some of the city’s low income groups are being displaced in favour of questionable infrastructure improvements and over-budget sports venues. The rise of these movements emerged in the context of the mega-events, which have been perceived as having channeled resources to the benefit of powerful political and economic actors. Therefore, the protests demonstrate a collective cry out against entrenched private interests in Brazil, such as the private bus operators, taking advantage of the established order at the expense of the majority of the population who have gotten the raw end of the deal in public services. The Free Pass Movement (Movimento Passe Livre), a movement against increased fares in mass transit, noted that: “Like a ghost that haunts cities leaving marks on the living space and memory, the popular uprisings around transportation assail the history of Brazilian metropolises since their formation … [The movements] are a worthy expression of rage against a system completely delivered to the logic of the commodity” (Movimento Passe Livre, 2013). As the protests quickly snowballed across Brazil, they underscored a change from a less obvert, more complacent public. Yet observers of Brazil’s urban situation knew that fragmented demonstrations, dissatisfaction and resistance movements had been spreading in urban areas (Maricato, 2013; Vainer, 2013).

For Carlos Vainer (2013), a renowned economist and sociologist, the spark that ignited the protests was the well-known adverse conditions in Brazilian cities. Similarly, long-time urbanist Ermínia Maricato (2013) argued that the main objectives of the protests and the conditions of Brazilian cities are inherently connected. Despite promises to transform this situation by recent progressive governments, decades of stagnation have affected Brazil’s cities and poor urban dwellers have experienced the worst consequences. Exacerbating this situation, the adoption of neoliberal ideals throughout the ‘90s has had serious repercussions in Brazilian cities. Neoliberalism “deepened and sharpened the known problems” inherited by “forty years of exclusionary developmentalism: favelization, informal, precarious or nonexistent services, deep inequalities, environmental degradation, urban violence, congestion and rising costs of public transport and urban segregation” (Vainer, 2013, section 3.3). As a result, the evident contradictions of the system gave rise to resistance movements that aim to overhaul the status quo in Brazilian cities. Following the first protests in São Paulo, President Dilma Rousseff announced that the government had heard the “voices for change” which gave “a direct message” to society standing for citizenship, education, health, high quality transportation and the right to participate: “This direct message from the streets stands for the right to influence in decisions at all government, legislature, and judicial levels” (Mendes, 2013). Still, the governments’ commitment to tackle the protesters’ demands have been challenged. The protests represent forgotten promises, “the resumption of important claims of struggle for basic social rights” and also “a sign that Brazilian society is very happy to have more money to buy more things, but that is not enough” (Rolnik, 2013b). The largest protests in Brazil in almost 20 years, the 2013 movements share similar ideals with the urban reform movements of the 1970s and 1980s. These movements questioned urban conditions in Brazilian cities, calling for urban reform based on the idea of the right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968). The urban social movements of the 1970s and 1980s helped to bring urban issues to centre stage, culminating in the massive demonstrations that led to the transition from military rule into a new democratic Constitution for the country in 1988. They also played a key role in the approval of the 2001 Statute of the City, an important Brazilian law that formally embraces the right to the city for all through participatory planning and attempts to improve life for city dwellers through planning based on ideals of social justice (Avritzer, 2010). Although the 2013 protests were a surprise to international audiences, like the earlier urban reform movements, they question urban conditions and demonstrate a clear dissatisfaction among many Brazilians with the wide separation between theory and practice in Brazil (Maricato, 2011). After 25 years of a return to democracy, political commitments to make progress on corruption, poor governance and the misuse of public spending have not been realized through tangible results. Frustrated by the public promises yet to be fulfilled, more than a million Brazilians came out in full force, demonstrating that this gap between theory and practice needs to be remedied. Beyond the general disparity between theory and practice, in the planning context this gap is even more readily evident and its nefarious results affect every aspect of the lives of urban dwellers daily. Indeed, the ideals of the urban reform movements have not resulted in real gains in addressing the myriad of difficulties of Brazilian urban life; the urban reform agenda has been left behind. And despite widespread praise of progressive legislation in Brazil such as the Statute of the City, the results have been discouraging, as I have described in the case of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro State (Friendly, 2013) and others have shown in other cities (Santana, 2011). For example, the application of public participation has been challenging while the implementation of planning tools that could put socially justice planning into use have been partial, at best. As a result, a gap between the original goals of the urban reform movement and local practice has become unmistakeable in Brazilian planning practice. The protests that emerged in June 2013 challenge not only particular planning issues including transportation, but also the poor application of proposals such as those made by the urban reform movements. As a result, these protests should be regarded as evidence of the fact that in Brazil’s cities, where the overwhelming majority of Brazilians live, conditions have not improved and tangible results have not been reached despite promises to achieve the right to the city for all. Bibliography Avritzer, L. (2010). “Democratizing Urban Policy in Brazil: Participation and the Right to the City.” In J. Gaventa & R. McGee (Eds.), Citizen Action and National Policy Reform: Making Change Happen. London: Zed Books, pp. 153-173. Castilho, C. (2013, June 25). “O Desafio da Complexidade na Crise das Manifestações de Rua.” Observatório da Imprensa Retrieved July 2, 2013, fromhttp://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/posts/view/o_desafio_da_complexidade_na_crise_das_manifestacoes_de_rua Friendly, A. (2013). “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil.” Planning Theory and Practice 14(2): 158-179. Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. Maricato, E. (2011). O Impasse da Política Urbana no Brasil. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes. Maricato, E. (2013). “É a Questão Urbana, Estúpido!”. In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Mendes, P. (2013, June 18). “Dilma Defende Protestos e Diz que Governo Ouve ‘Vozes pela Mudança’.” O Globo. Movimento Passe Livre (2013). “Não Começou em Salvador, Não Vai Terminar em São Paulo.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Rolnik, R. (2013a). “Apresentação: As Vozes das Ruas: As Revoltas de Junho e suas Interpretações.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Rolnik, R. (2013b) “São Paulo: A Voz das Ruas e a Oportunidade de Mudanças.” Blog da Raquel Rolnik. Accessed on July 4, 2013 at http://raquelrolnik.wordpress.com/2013/06/18/sao-paulo-a-voz-das-ruas-e-a-oportunidade-de-mudancas. Santana, C. R. S. (2011). Aplicação do Estatuto da Cidade em Salvador no Século XXI: Discurso e a Prática. Unpublished Masters, Universidade Salvador, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento Regional e Urbano, Salvador. Vainer, C. (2013). “Quando a Cidade vai às Ruas.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Williamson, T. (2013, June 19). “It’s Just the Beginning; Change Will Come.” The New York Times. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly