|

Originally posted in Panoramas.

Protest movements in response to a range of issues have been in the spotlight in Brazil over the past three years, prompting considerable discussion about the future of collective action for the country. Drawing on research that occurred before the large-scale 2013 mobilizations occurred, this article in Latin American Research Review attempts to make sense of a perceived decline in social movement activity in urban centres in Brazil, arguing that such alterations result from a changing political context. It attempts to make sense of the many waves of civil society activity in the urban context, based on the idea of a cycle of protests (Tarrow, 1994). Brazil is a particular case where urban social movement activity has been much less significant in recent years than the social movements that emerged in the countryside such as the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), a phenomenon that Souza (2016) has discussed recently. The 2013 protests were the first massive protests in Brazilian cities since at least the Diretas Já movement in 1983-84 (the campaign for direct elections that ended 20 years of military rule). The article focuses on Niterói, a city of about a half-million people across the bay from Rio de Janeiro. Although civil society flourished until the 1990s in Niterói, many interviewees noted that the dynamism that had previously existed in the city was no longer present. Some referred to passivity, others mentioned retracted participation, while others talked about the movements’ “decay.” Given the need for a vibrant civil society in taking forward the goals of the urban reform movement in Brazil, this concern prompted an exploration to more analytically describe the nature of this decay. The urban reform movement, discussed in this article, initiated in the 1980s and composed of popular movements, neighborhood associations, NGOs, trade unions and professional organizations, helped to formulate a proposal for urban reform in the National Constituent Assembly. Ultimately, the movement was integral in helping to approve the Statute of the City in 2001, the national law that provides planning tools for cities based on a social justice approach. As a result, part of this interest in social movements stemmed from a contention of the important role of civil society in both the Brazilian Constitution (1988) building process and in the approval of the Statute of the City. In that sense, this is a very urban story that has played out in Brazil over several decades. This article was written and researched well before Brazilians came out in droves to protest, in part, a gap between theory and practice in June 2013. The June 2013 protests erupted in São Paulo against rising bus fares and were followed by similar protests across Brazil, highlighting the urban nature of the protests (Friendly, 2016). Since writing this article, much has changed in the world of urban social movements in Brazil as well as the political context. As the world watched Brazil prepare for and host the Rio Olympic Games, the economy slumped alongside an ongoing corruption crisis that resulted in, among other things, President Dilma Rousseff being removed from office. In addition to the protests that began in June 2013 to oppose rising bus fares, Brazilians have continued going to the streets to oppose rising transportation costs, corruption, the right to the city in general and the poor economic situation. Following Rousseff’s impeachment, protesters haven’t let up against Michel Temer’s interim government. One of the interesting things that has emerged in all of these events is that the protests at various points in time have come from both the political right and left. These events highlight a key conclusion of the article: that civil society changes and adapts based on the political context, including external opportunities. This approach connects the emergence and decline of protest cycles with political, institutional and cultural changes as key elements in understanding these changing dynamics. Given all the changes that have taken place over the past couple of years in Brazil, it is indeed a key moment for the country, but it is unlikely that civil society in Brazil will be as complacent as perceived in the case of Niterói. There is no question that civil society is playing a key role, but as this paper has argued, the political situation has also changed, redrawing a central element to these shifting dynamics. References Friendly, Abigail 2016 “Urban Policy, Social Movements and the Right to the City in Brazil.” Latin American Perspectives doi: 0094582X16675572. Souza, Marcel Lopes de 2016 “Social Movements in Brazil in Urban and Rural Contexts: Potentials, Limits and “Paradoxes.” In The Political System of Brazil, edited by D. de la Fontaine and T. Stehnken, 229-252. New York: Springer. Tarrow, Sidney 1994 Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Friendly, Abigail. 2016. “The Changing Landscape of Civil Society in Niterói, Brazil.” Latin American Research Review51(1): 218-241. DOI: 10.1353/lar.2016.0012

0 Comments

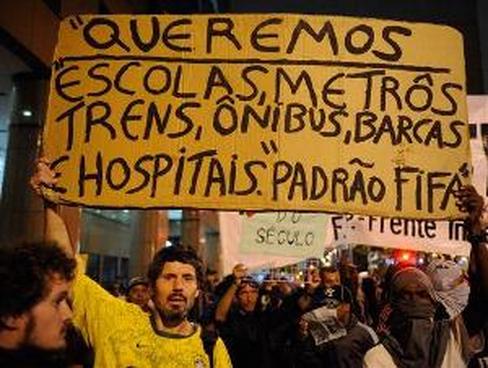

Questioning the mega-event legacy: Planning and unkept promises in Brazil's world cup of 20146/26/2014 Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com As the opening of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil unfolds, protests have once again raged against the excessive spending on the sports event rather than on much-needed public sector services. In part, the huge funds spent on the World Cup helped to fuel the June 2013 protests across Brazil, among other issues.1 On June 15, 2014, protesters demonstrated in Rio with the slogan ‘se não tiver direitos, não vai ter Copa’ (If there are no rights, there won’t be a World Cup) (see Figure 1). Unkept promises As a backdrop to the protests that started in June 2013 and more recently surrounding the World Cup, a developing story in the planning context is the promise by the Brazilian government to deliver infrastructure to support the World Cup and the disappointing result of unkept promises. This disconnect between promised public infrastructure projects – such as various public transport systems – and the many delayed or yet-to-be started projects, is an intriguing story for planners watching the World Cup develop. This is referred to by Thornley (2012: 207) as the “dark side” of legacy, including the displacement of uses, rights and residents to make way for venues as well as the lost projects from which funds are ultimately diverted. For example, in the Brazilian amazonian city of Manaus, an urban transport system that included a monorail and a BRT was promised yet the project never began. Manaus’ airport is also being upgraded, but was not ready in time for beginning of the World Cup. Many of the longer-term investments in public transportation have also been scrapped, such as the high speed train linking Rio and São Paulo. Projected to begin for the World Cup, the train will only be finished by 2020, if at all. There has also been criticism of the stadiums that will be used only a handful of times for World Cup matches yet will be unlikely to host a team once the games are over. In 2010, the government promised a ‘matrix of responsibilities’ in the 12 cities holding World Cup games.2 In addition to the obvious stadiums and urban transport systems such as BRTs, airports, ports and hotels were promised. In 2010, the estimated investment in infrastructure (urban mobility, airports and ports) was US$8 billion [R$17.7 billion] and all projects were to be ready by December 2013. Delays, cost overruns, lawsuits and corruption scandals have put a damper on the World Cup festivities: “At 100 days before the World Cup, reality proves to be quite different from what was projected on paper: only 18% of infrastructure projects were delivered and investment fell to [US$6.5 billion] R$14.7 billion – cut by [US$1.5 billion] R$3 billion” (Marques, 2014). In the updated matrix in September, there were 45 projects listed in the area of urban mobility (10 of these are improvements surrounding the stadiums), 12 in stadiums, 30 in airports and 6 in airports. Brazil has spent about US$ 11 billion (over $25 billion reais) on infrastructure related to the World Cup. A third of this cost went to both building and refashioning stadiums in the 12 host cities. Despite spending so much on the World Cup, Brazil has delivered only a fraction of the projects it promised to undertake, and many of those are unfinished, such as Rio’s international airport. Many such projects are unfinished and others never left the drawing board. The newspaper Folha de São Pauloreported in May 2014 that only 41% of the planned projects had been completed (or 68 out of 167). This includes the completion of 10% of urban transport projects and 49% of airport and port projects. In addition, 88 projects are incomplete or will be left for after the World Cup to be completed and 11 were entirely abandoned. To get this data, Folha “listed and checked the progress of all actions contained in the so-called ‘matrix of responsibilities’” (Folha de São Paulo, 2014). In addition, despite a decrease in investments, the majority of the projects in the 2010 document increased in cost: “in other words, the decrease in the total value occurred principally because of the exclusion of large projects and not because of the cheapening of the works” (Marques, 2014). Even worse, there has been little official information released about the specifics of the unfinished projects and the percentage compared to the total expected in 2010. While the updated matrix of responsibilities is available online, it shows the volume of funds “projected” but not the amount spent on the projects, making it necsesary to turn to media reports to show infrastructure projects that are delayed or not happening. As Ricardo Setti noted recently in column in Veja, by disclosing the amount of money invested without detailing the specifics, the government manufactures a magical account: “Magic makes most projects receive the generic stamp of ‘adequate progress’” (Setti, 2014). Overall, the last priority in the leadup to the World Cup was transportation – after stadiums and airports. The solution for notoriously bad congestion in some cities was to declare holidays for the days with games. In the second week of the games, Rio had only two regular business days. Rio’s much-lauded BRT will only be partly operational for the World Cup, with only some of its 45 stations running. BRTs and light rail projects in other cities have been scrapped. Although the problem is arguably not only related to the World Cup, the promise of many large-scale infrastructure projects such as BRTs is deceptive. The legacy of the games for whom? The legacy of the games is often touted as a rationale for hosting such events, together with legitimizing the spatial transformations of the city. Indeed, the expericence of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics helped to perpetuate the notion of the wider urban legacy of the games while “images of empty venues post-games raised questions about the economic and environmental costs of mega-events and the benefits to local populations” (Brownhill, et al., 2013: 112). The idea that hosting mega-events such as the World Cup will result in few social benefits has been pervasive this time around, as has been the case in past events. As a BBC story noted recently, although Brazil has a duty to put on a good show, “what about the government’s “duty” to its own people?” (Davies, 2014). In a critque of use of the term ‘legacy’ for the city of Rio, Magalhães (2013: 94) notes that its use appears in numersous situations where an explanation of the urban interventions in Rio was deemed necessary through a repertoire of removals, which have resulted in changes in the use of city space and the displacement of some favela residents. For that reason, Brownhill et al (2013) not that such legacies are political, with different possible visions between the initial drawing up of plans and the actual delivery of those plans. Indeed, in contrast to the role such events play as vehicles for development, much of the literature has characterized mega-events as “powerful engines in the neo-liberal reconfiguration of the city, promoting the privatization and commodification of urban space, and the implementation of market-oriented economic policies” (Sánchez & Broudehoux, 2013: 135). In the case of the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, Pillay and Bass (2008: 331) note that: Mega-events are often used as ‘spectacles’ that can best be understood as either instruments of hegemonic power, or displays of urban ‘boosterism’ by economic elites wed to a particularly narrow-minded pro-growth vision of the city. As such, these events are often seen as no more than public relations ventures far removed from the realities of urban problems and challenges. Similarly, in reference to the case of Rio (probably the most widely studied city in Brazil in relation to the mega-events because of the coming Olympics in 2016), Sánchez and Broudehoux (2013) argue that mega-events are being instrumentalized by local political and economic elites, creating an exclusive vision of urban regeneration. Ultimately, the authors argue, this has paved the way for state-assisted privatization and commodification of the urban realm, fulfilling the needs of capital while intensifying socio-spatial segregation, inequality and social conflicts. Carlos Vainer (2011) has made the argument that mega-events are part of a process that has led to a city of exception, a new type of urban regime or reconfiguration of power structures at the local and national levels which imposes a new neo-liberal order marked by authoritarianism and exceptionalism: “The mega-events realized in its intense and full form, the city of exception. In this city, everything goes outside the formal institutional mechanisms… The city of mega-events is the city of ad hoc decisions, exemptions, special permits…” Drawing on Agamben’s (2005) idea of a state of exception, such exceptions turn into the rule as they become key tools to bypass the democratic political process in implementing mega projects. In this scheme, the General Law of the World Cup (Lei Geral da Copa) acts as an exemption. During the World Cup, some Brazilian laws have even been temporarily revoked. One of the most noteworthy of these exemptions was to reverse the ban on alcohol in stadiums, allowing Budweiser (a FIFA sponsor) to sell beer at World Cup games.

This discourse about the city of exceptions forces one to think about who the investments are benefitting, even as mega-events are touted as profiting the city as a whole. So what can we expect for the 2016 Olympics? Of course, all eyes will be on Rio as 2016 nears. 1 See my post on the protests in 2013 here. 2 See www.copa2014.gov.br/en/brasilecopa/sobreacopa/matriz-responsabilidades. References Agamben, G. (2005). State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Brownhill, S., Keivani, R., & Pereira, G. (2013). “Olympic Legacies and City Development Strategies in London and Rio; Beyond the Carnival Mask?” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 5(2): 111-131. Davies, W. (2014, June 16). “Has Brazil proved World Cup doubters wrong?” BBC. Folha de São Paulo (2014, May 13). “A 30 Dias da Copa, Metade das Metas Não Foi Cumprida.” Folha de São Paulo. Magalhães, A. (2013). “O ‘Legado” dos Megaeventos Esportivos: A Reatualização da Remoção de Favelas no Rio de Janeiro.” Horizontes Antropológicos 19(40): 89-118. Marques, F. (2014, March 4). “A 100 Dias da Copa, Só 18% das Obras de Infraestrutura Foram Entregues.” O Globo. Pillay, U., & Bass, O. (2008). “Mega-events as a Response to Poverty Reduction: The 2010 FIFA World Cup and its Urban Development Implications.” Urban Forum 19(3): 329-346. Sánchez, F., & Broudehoux, A.-M. (2013). “Mega-Events and Urban Regeneration in Rio de Janeiro: Planning in a State of Emergency.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 5(2): 132-153. Setti, R. (2014, March 7). “VEJAM O RIDÍCULO: O trem-bala São Paulo-Rio, que nem foi licitado — e talvez nunca venha a existir -, consta na papelada do governo como estando ‘com andamento adequado’.” Veja. Thornley, A. (2012). “The London 2012 Olympics: What Legacy?” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 4(2): 206-210. Vainer, C. (2011). Cidade de Exceção: Reflexões a Partir do Rio de Janeiro. Paper presented at the XIV Encontro Nacional da ANPUR, Rio de Janeiro, May 23-27. Brazilian protests in the planning context: How can we narrow the gap between theory and practice?11/8/2013 Originally posted at http://planninglatinamerica.wordpress.com Recently the very real challenges of life in Brazilian cities became evident to international audiences as Brazilians took to the streets in full force to protest poor delivery of public services, widespread mismanagement of government funds and general dissatisfaction with the status quo of political representation.Starting in June 2013, the demonstrations were sparked by an increase in bus fares in São Paulo, but quickly spread throughout the country denouncing a host of problems that plague Brazilian cities including violence, inadequate sanitation and housing, and a slow daily commute in crowded, often dangerous and consistently unreliable transportation. As the protests expanded to other Brazilian cities, the complexity of the issues raised by the protesters became visible to observers (Castilho, 2003). These protests basically centre on two questions: what type of city is lived in the present and what is desired for city life in the future. The protests also stand for demands for the right to the city: “the right to mobility … is also the right to the city, to collective decision-making, to opportunity, to justice” (Williamson, 2013). In addition, the demonstrations revolve around questions of democracy. As the urbanist Raquel Rolnik (Rolnik, 2013b) observed in a blog post, “the desire to participate also seemed very visible. People want to be consulted, they want their views to be taken into account. Representative democracy in Brazil is clearly experiencing a crisis.” The Brazilian protesters were moved by a latent impulse to change public services, including transportation, education and health, but ultimately to transform Brazilian society and how political power is used. As a result, the protests are anti-status quo (Vainer, 2013). As the demonstrations mushroomed, they transformed into a movement against bad politics, a persistent malady of Brazilian society throughout its history. The people’s challenge is not against a particular political party, but against all those in power. In fact, political party flags were banned from many of the protests on the streets. For observers, what brought the movements together in part was a push against the dominance of the ruling political powers such as those in charge of organizing and funding mega-events like the World Cup, the media and large corporations. Although protests took place in dozens of metropolitan areas across Brazil, the biggest demonstrations were in Rio, where the most drastic results of misspending in preparation for the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics have occurred at the same time as some of the city’s low income groups are being displaced in favour of questionable infrastructure improvements and over-budget sports venues. The rise of these movements emerged in the context of the mega-events, which have been perceived as having channeled resources to the benefit of powerful political and economic actors. Therefore, the protests demonstrate a collective cry out against entrenched private interests in Brazil, such as the private bus operators, taking advantage of the established order at the expense of the majority of the population who have gotten the raw end of the deal in public services. The Free Pass Movement (Movimento Passe Livre), a movement against increased fares in mass transit, noted that: “Like a ghost that haunts cities leaving marks on the living space and memory, the popular uprisings around transportation assail the history of Brazilian metropolises since their formation … [The movements] are a worthy expression of rage against a system completely delivered to the logic of the commodity” (Movimento Passe Livre, 2013). As the protests quickly snowballed across Brazil, they underscored a change from a less obvert, more complacent public. Yet observers of Brazil’s urban situation knew that fragmented demonstrations, dissatisfaction and resistance movements had been spreading in urban areas (Maricato, 2013; Vainer, 2013).

For Carlos Vainer (2013), a renowned economist and sociologist, the spark that ignited the protests was the well-known adverse conditions in Brazilian cities. Similarly, long-time urbanist Ermínia Maricato (2013) argued that the main objectives of the protests and the conditions of Brazilian cities are inherently connected. Despite promises to transform this situation by recent progressive governments, decades of stagnation have affected Brazil’s cities and poor urban dwellers have experienced the worst consequences. Exacerbating this situation, the adoption of neoliberal ideals throughout the ‘90s has had serious repercussions in Brazilian cities. Neoliberalism “deepened and sharpened the known problems” inherited by “forty years of exclusionary developmentalism: favelization, informal, precarious or nonexistent services, deep inequalities, environmental degradation, urban violence, congestion and rising costs of public transport and urban segregation” (Vainer, 2013, section 3.3). As a result, the evident contradictions of the system gave rise to resistance movements that aim to overhaul the status quo in Brazilian cities. Following the first protests in São Paulo, President Dilma Rousseff announced that the government had heard the “voices for change” which gave “a direct message” to society standing for citizenship, education, health, high quality transportation and the right to participate: “This direct message from the streets stands for the right to influence in decisions at all government, legislature, and judicial levels” (Mendes, 2013). Still, the governments’ commitment to tackle the protesters’ demands have been challenged. The protests represent forgotten promises, “the resumption of important claims of struggle for basic social rights” and also “a sign that Brazilian society is very happy to have more money to buy more things, but that is not enough” (Rolnik, 2013b). The largest protests in Brazil in almost 20 years, the 2013 movements share similar ideals with the urban reform movements of the 1970s and 1980s. These movements questioned urban conditions in Brazilian cities, calling for urban reform based on the idea of the right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968). The urban social movements of the 1970s and 1980s helped to bring urban issues to centre stage, culminating in the massive demonstrations that led to the transition from military rule into a new democratic Constitution for the country in 1988. They also played a key role in the approval of the 2001 Statute of the City, an important Brazilian law that formally embraces the right to the city for all through participatory planning and attempts to improve life for city dwellers through planning based on ideals of social justice (Avritzer, 2010). Although the 2013 protests were a surprise to international audiences, like the earlier urban reform movements, they question urban conditions and demonstrate a clear dissatisfaction among many Brazilians with the wide separation between theory and practice in Brazil (Maricato, 2011). After 25 years of a return to democracy, political commitments to make progress on corruption, poor governance and the misuse of public spending have not been realized through tangible results. Frustrated by the public promises yet to be fulfilled, more than a million Brazilians came out in full force, demonstrating that this gap between theory and practice needs to be remedied. Beyond the general disparity between theory and practice, in the planning context this gap is even more readily evident and its nefarious results affect every aspect of the lives of urban dwellers daily. Indeed, the ideals of the urban reform movements have not resulted in real gains in addressing the myriad of difficulties of Brazilian urban life; the urban reform agenda has been left behind. And despite widespread praise of progressive legislation in Brazil such as the Statute of the City, the results have been discouraging, as I have described in the case of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro State (Friendly, 2013) and others have shown in other cities (Santana, 2011). For example, the application of public participation has been challenging while the implementation of planning tools that could put socially justice planning into use have been partial, at best. As a result, a gap between the original goals of the urban reform movement and local practice has become unmistakeable in Brazilian planning practice. The protests that emerged in June 2013 challenge not only particular planning issues including transportation, but also the poor application of proposals such as those made by the urban reform movements. As a result, these protests should be regarded as evidence of the fact that in Brazil’s cities, where the overwhelming majority of Brazilians live, conditions have not improved and tangible results have not been reached despite promises to achieve the right to the city for all. Bibliography Avritzer, L. (2010). “Democratizing Urban Policy in Brazil: Participation and the Right to the City.” In J. Gaventa & R. McGee (Eds.), Citizen Action and National Policy Reform: Making Change Happen. London: Zed Books, pp. 153-173. Castilho, C. (2013, June 25). “O Desafio da Complexidade na Crise das Manifestações de Rua.” Observatório da Imprensa Retrieved July 2, 2013, fromhttp://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/posts/view/o_desafio_da_complexidade_na_crise_das_manifestacoes_de_rua Friendly, A. (2013). “The Right to the City: Theory and Practice in Brazil.” Planning Theory and Practice 14(2): 158-179. Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. Maricato, E. (2011). O Impasse da Política Urbana no Brasil. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes. Maricato, E. (2013). “É a Questão Urbana, Estúpido!”. In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Mendes, P. (2013, June 18). “Dilma Defende Protestos e Diz que Governo Ouve ‘Vozes pela Mudança’.” O Globo. Movimento Passe Livre (2013). “Não Começou em Salvador, Não Vai Terminar em São Paulo.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Rolnik, R. (2013a). “Apresentação: As Vozes das Ruas: As Revoltas de Junho e suas Interpretações.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Rolnik, R. (2013b) “São Paulo: A Voz das Ruas e a Oportunidade de Mudanças.” Blog da Raquel Rolnik. Accessed on July 4, 2013 at http://raquelrolnik.wordpress.com/2013/06/18/sao-paulo-a-voz-das-ruas-e-a-oportunidade-de-mudancas. Santana, C. R. S. (2011). Aplicação do Estatuto da Cidade em Salvador no Século XXI: Discurso e a Prática. Unpublished Masters, Universidade Salvador, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento Regional e Urbano, Salvador. Vainer, C. (2013). “Quando a Cidade vai às Ruas.” In C. Vainer, D. Harvey, E. Maricato, F. Brito, J. A. Peschanski, J. L. S. Maior, L. Sakamoto, L. Secco, M. L. Iasi, M. Davis, P. R. d. Oliveira, R. Rolnik, R. Braga, S. Viana, S. Žižek & V. A. d. Lima (Eds.), Cidades Rebeldes: Passe Livre e as Manifestações que Tomaram as Ruas do Brasil [Kindle version]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial. Williamson, T. (2013, June 19). “It’s Just the Beginning; Change Will Come.” The New York Times. |

Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly